THE NEGLECT OF CONFESSION IN CONTEMPORARY WORSHIP MUSIC

Artistic Theologian 10 (2023): 43-64

Braden McKinley is a Ph.D. student in Church Music and Worship at Southwestern Baptist

Theological Seminary. He serves as Worship Pastor at Central Church in Collierville, TN.

Worship at its core is a proclamation and enactment of God’s salvation narrative.2 As such, worship encompasses the three-fold work of salvation in how its content reflects on justification, nourishes sanctification, and anticipates glorification. In this way, progressive sanctification is an underlying intent of worship practice. Every liturgical gathering is a Spiritenabled opportunity for the worshiping community to grow in holiness.

While Scripture instructs that confession of sin is a necessary component of progressive sanctification, found particularly in Matthew 6:9–13 (the Lord’s Prayer), 1 John 1:9, and James 5:16, this biblical foundation appears to be obscured in the sphere of contemporary worship music (CWM). Lester Ruth and Swee Hong Lim’s informative and helpful Lovin’ on Jesus shares a convicting insight that between 1989 and 2016 there was a considerable absence of CWM songs that function as a confession of sin. The authors write, “There is very little confession of sin, failure, or fault and absolutely no laments of complaints or distress with God.”3

The purpose of this study is to evaluate more closely Lim and Ruth’s observation indicating a deficiency of sin-confession songs in CWM. To undergird this discussion, I will briefly present a biblical understanding of confession. Following this, I will report findings from evaluating the top one hundred worship songs documented through Christian Copyright Licensing International (CCLI), with special attention to mention of sin, confession, and lament.4 From these results, I will draw conclusions regarding the form and content of confession in CWM, and devote discussion concerning the underlying theological and philosophical influences contributing to this trend. I will argue that while confession of sin in CWM is ostensibly practiced, it is altered into a reflective notion rather than a present action.

A BIBLICAL UNDERSTANDING OF CONFESSION OF SIN

Biblical confession is always God-centered, for it is a component of a full response to God’s self-revelation of his all-surpassing worth.5 Bryan Chapell aptly notes, “Recognition of who God truly is leads to awareness of who we really are.”6 Thus, in Scripture the concept of confession unfolds in two aspects. First is the aspect of confessing the sovereign holiness of God, including a creedal element affirming his nature, character, and saving acts.7 The second aspect is confessing human unworthiness to be in His presence. To confess the name of the Lord is to be in agreement and alignment with God in his self-revelation and commands, thereby exposing human sin. When confessing the sovereign, glorious, redemptive qualities of God, one’s unholiness and unworthiness become all the more pronounced. Two scriptures in particular illustrate this pattern of response. The first is Isaiah’s encounter with God in Isaiah 6:1–8, where upon witnessing God’s unparalleled glory he responds with “Woe is me! For I am lost.” The second example is in response to Jesus’s revelation through the miraculous catch of fish in Luke 5. As Simon Peter witnesses Jesus’s divinity, he implores, “Depart from me, for I am a sinful man, O Lord” (Lk 5:8). Common to each instance, both Isaiah and Peter are struck by the awareness they have inadvertently encroached on forbidden territory as sinful creatures in the presence of Almighty God.8

Building upon this biblical pattern, multiple psalms and prayers of confession for private and corporate use appear in the biblical canon. In the Old Testament, David’s Psalms 32 and 51, for example, express laments over his violation of the Law and his fervent desire to restore fellowship with God. Psalms such as 78 and 106, as well as Nehemiah 9, address vcorporate, national sin that narrate the cycles of Yahweh’s redemption and faithfulness that were met by Israel’s further rebellion. Other corporate confessions of sin expressed by an individual include Nehemiah 1 and Daniel 9.

The New Testament church gathered within the all-encompassing reality of Christ’s redemptive work by the cross, resurrection, and ongoing intercession, establishing the covenant and ushering in the Church age. These realities could seemingly make ongoing corporate confession of sin appear unnecessary. Yet New Testament theology describes a continuing tension with the flesh being prone to sin as one strives to walk with the Spirit.9 Thus James 5:16 instructs: “Therefore, confess your sins to one another and pray for one another, that you may be healed.” Likewise John 1:9 teaches: “If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just to forgive us our sins and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness.” Biblical confession is not to induce self pity and self-deprecation or striving to earn mercy but is a means to be renewed in grace and mature in sanctification.10

CONFESSION IN LITURGY

Bryan Chapell starkly contends, “If there has been no confession of sin then there has been no real apprehension of God.”11 As biblical liturgy rehearses the gospel, embodying what is commonly known as gospel-shaped worship,12 confession assumes a vital role in the gospel enactment while lending manifold implications for the divine-human dialogue taking place in worship.13 The gospel enactment of worship carries the worshiper through the contours of the gospel by sequencing its worship events to follow the narrative logic of salvation history. Its purpose is for the congregation to be regularly renewed in the gospel realities of the new covenant set forth in Christ.14 Furthermore, repeated habits and rituals assembled by this particular gospel narrative gradually form belief, model practices of spiritual formation, and shape desire towards God.15 Naturally, the liturgical parallel to the salvation narrative component of the Fall is an explicit acknowledgement of humankind’s failure and depraved condition outside of God’s gracious intervention.16 Liturgical elements could include corporate recited confession of sin, individual confession facilitated by a pastor, congregational hymns or songs of confession, or intercessory prayer (corporate and individual) for the sins of each other.17 Maintaining these practices not only preserves the integrity of the full gospel narrative in worship, but also these practices are rich with theological implications that are both instructional and formative for sanctification. Through the pattern of confession and assurance of pardon, one is reoriented to the reality that worship does not come naturally due to our sin condition; moreover, worship itself is a gift bestowed and enabled by God’s grace.18 Confession also serves to reorient one to the reality of sin, which causes brokenness and discord on both minute and cosmic levels.19 Lastly, confession is a reorientation to the fact that Christ has once and for all atoned for the sins of the world. As the believer still undergoes conflict with the flesh and regularly returns to Christ in confession, the reality of the atonement is impressed on the affections of the believer.20

PSALM 51: A MODEL FOR BIBLICAL CONFESSION

Five key aspects of biblical confession are imbedded in David’s prayer in Psalm 51. The first is acknowledgment of sin: “Against you, you only, have I sinned and done what is evil in your sight” (Ps 51:4a). The second is a plea for forgiveness: “Wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow” (Ps 51:7b). The third is lament over one’s sin: “For I know my transgressions, and my sin is ever before me” (Ps 51:3). he fourth aspect is a resolve to flee from sin and restore one’s relationship to God: “Then will you delight in right sacrifices, in burnt offerings and whole burnt offerings” (Ps 51:19). The final aspect is appealing to the grace and mercy of God: “According to your abundant mercy blot out my transgressions” (Ps 51:1b). The prayer of confession of sin offered in the Book of Common Prayer well follows this biblical model:

Most merciful God, Address God

We confess that we have sinned against you Acknowledgement of sin

In thought, word, and deed,

By what we have done,

And by what we have left undone.

We have not loved you will our whole heart;

We have not loved our neighbor as ourselves.

We are truly sorry and we humbly repent. Lament for sin

For the sake of your Son Jesus Christ, Appeal to God’s grace

Have mercy on us and forgive us; Plea for forgiveness

That we may delight in your will, Resolve to flee from sin

And walk in your ways,

To the glory of your Name. Amen.21

EVALUATION OF CCLI’S TOP 100 WORSHIP

SONGS REGARDING CONFESSION OF SIN

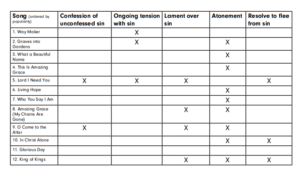

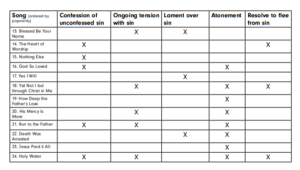

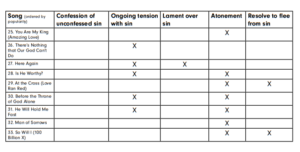

While there are multiple components that contribute to the liturgical phenomenon of “contemporary worship,” song lyrics provide a concrete documentation that depicts an ethos of popular trends in contemporary worship.22 Under this guise, this discussion will now shift focus to the current canon of popular CWM songs for congregational use to determine their feasibility to function as corporate confession of sin.23 The subsequent criteria have been used to identify which songs relate in some way to the concept of confession: (1) songs that reference a depraved human nature, (2) songs that express a plea for forgiveness or show sin as an ongoing struggle, (3) songs that express regret or lament over sin and its effects, and (4) songs that describe or appeal to the atonement as payment for sin. Of the one hundred songs on this list, thirty-three meet at least one of these criteria. The lyrical content of those songs will now be examined by answering a set of questions that correlate to the aspects of biblical confession found in Psalm 51.24

QUESTION 1: DO THE SONGS CONFESS PREVIOUSLY

UNCONFESSED SIN ASKING FOR FORGIVENESS?

Of the thirty-three songs chosen, only seven remotely function in a way to ask for forgiveness for previously unforgiven sin. The most compelling example is the song “Lord I Need You” by Matt Maher. Its lyrics contain direct confessional language: “Lord I come, I confess, bowing here I find my rest,” and “Where sin runs deep, Your grace is more,” and finally the chorus, “Lord I need You, oh I need you, every hour I need You” as a direct echo of the Hawks and Lowry 1872 hymn, “I Need Thee Every Hour.” A second and relatively solid example of confession also by Matt Maher, in collaboration with Cody Carnes, is their song “Run to the Father.” The first verse sings:

I’ve carried a burden for too long on my own

I wasn’t created to bear it alone

I hear your invitation to let it all go

I see it now; I’m laying it down

And I know that I need you.

The text goes on to evoke the imagery of the return of the prodigal son in Luke 15 with the words, “I run to the Father, I fall into grace. I’m done with the hiding, no reason to wait. My heart needs a surgeon, my soul needs a friend.” The song depicts the action of turning to God for forgiveness not as a one-time event, but as a consistent rhythm of the Christian life shown through the lyrics, “So I’ll run to the Father again and again and again” (emphasis mine). 25

Within the scope of songs pertaining to the first question, two additional subcategories of song loosely function as confession of sin. The first grouping contains songs that confess one’s diminishing reverence and waning adoration in musical worship. Matt Redman’s “The Heart of Worship” and Carnes’s “Nothing Else” both express this inward sentiment and contrition. Referencing worship, Redman’s text reads: “I’m sorry, Lord, for the thing I’ve made it—when it’s all about you, it’s all about you, Jesus.”26 Carnes’s song conveys a longing for rekindled intimacy with the Savior: “I’m sorry when I’ve just gone through the motions; I’m sorry when I just sang another song. Take me back to where we started, I open up my heart to You.”27

The second grouping of songs are those with lyrical imagery of an altar call summoning the unbeliever to repentance, yet these lyrics can also easily apply to the believer approaching God in confession. These texts induce the sense of a cathartic release of bringing one’s burden of sin and brokenness to God in an act of contrition, confession, and in some cases, conversion. A prime example is the song “O Come to the Altar” with the chorus lyrics: “O Come to the altar, the Father’s arms are open wide. Forgiveness was bought with the precious blood of Jesus Christ.” The verse lyrics amplify a sense of beckoning: “Are you hurting and broken within? Overwhelmed by the weight of your sin? Jesus is calling.”28 The dual focus of an altar call and confession is not made explicit in the lyrics but appears to be implied. We The Kingdom’s “God So Loved” also provides an apt example: “Come all you weary, come all you thirsty, come to the well that never runs dry.

. . . Bring all your failures, bring your addictions, come lay them down at the foot of the cross.” The text proceeds to proclaim the gospel promise of John 3:16: “For God so loved the world that He gave us, His one and only Son to save us, whoever believes in Him will live forever.”29

While none of the previously described songs meet all the criteria of biblical confession set forth in Psalm 51, these songs still bring sin into the vocabulary of congregational song texts, which is a necessary and positive trajectory.

QUESTION 2: DO THE SONGS DEPICT SIN

TO BE AN ONGOING STRUGGLE?

While thirteen songs of the thirty-three songs reference this second question, the idea of sin as a present reality is mainly implied and mostly vague in description. A fitting example of such a nebulous idea of present sin appears in the song “Way Maker” with the lyrics: “You are here, healing every heart. I worship you; I worship you.” In subsequent verses, “healing every heart” is changed to “mending every heart.”30 The words “mending” and “healing” imply there is some form of brokenness that needs be dealt with in the present, yet the cause and nature of the brokenness is unclear. Elevation Worship’s “Graves into Gardens” provides a second lyrical example suggesting an impression of ongoing struggles with sin: “I’m not afraid to show you my weakness. My failures and flaws, you’ve seen them all, and you still call me friend.”31 The song builds to a climactic bridge offering biblical imagery of rescue and resurrection: mourning to dancing, bones into armies, seas into highways, and the song’s title phrase, graves into gardens. Although not overtly described within the text, the impression that God will continue his work of rescue and renewal despite one’s continual proneness to spiritual weakness and wandering is implied. Yet the unclear nature of the text could lend itself to a myriad of interpretations.

There are, however, several biblically rooted texts within the current canon of popular CWM songs that depict sin as an ongoing reality. One excellent example is Matt Boswell and Matt Papa’s modern hymn “His Mercy Is More,” in which the lyrics concluding each refrain read “Our sins they are many, his mercy is more.”32 The lyric choice of “are many” instead of “were many” communicates sin to be a present actuality rather than a past problem. Yet the hymn does not wallow in self-deprecation, but rather the verses are rich in scriptural references that affirm God’s grace and forgiveness.33 In a similar vein, Andrew Peterson’s “Is He Worthy?,” based on Revelation 5, depicts sin and its effects as a present reality for the Church awaiting Christ’s return. Peterson’s lyrical device of a call and response effectively expresses the Church’s felt tension of living by faith in Christ in the midst of the ongoing brokenness and sin that plagues humanity. The lyrics read:

(Call) Do you feel the world is broken?

(Response) We do.

(Call) Do you feel the shadows deepen?

(Response) We do.

(Call) But do you know that all the dark

Won’t stop the light from getting through?

(Response) We do.

(Call) Do you wish that you could see it all made new?

(Response) We do.34

The text continues to affirm God’s immanent salvation and the Church’s secure hope through Christ’s atoning work. The lyrics culminate in depicting the heavenly vision of the throne room of God in Revelation 5. This text and “His Mercy Is More” both fittingly communicate a present conflict with sin and are thus the best available options within this category of song.

QUESTION 3: DO THE SONGS EXPRESS LAMENT

OVER SIN AND ITS EFFECTS?

Of the thirty-three songs identified, only seven nebulously imply lament over sin. Moreover, none of these songs directly mention sin as the source of lament but instead focus on embracing human emotional frailty. A pointed example is the song “Yes I Will” with the lyrics, “Yes I will, lift You high in the lowest valley. Yes I will, sing for joy when my heart is heavy.”35 This text acknowledges a general sense of human frailty, internal discord, and heartache, but nowhere does the text indicate sin as the source of these ailments. A second common characteristic of songs within this category is the acknowledgment of brokenness and unrest, followed by an affirmation of God’s salvation in a lyrical turn of events. Elevation Worship’s “Here Again” well demonstrates this pattern. Upon lamenting that “I’m not enough” outside of God’s presence predicated upon a feeling of walking through a valley of weakness, the text turns to hope in God’s salvation: “Not for a minute was I forsaken, the Lord is in this place. Come Holy Spirit, dry bones awaken, the Lord is in this place.”36 In addition to the aforementioned songs, some songs convey a reflective lament over sin, referencing the lament one experienced at a certain time in the past. Notable examples include “Death Was Arrested” with the lyrics “Alone in my sorrow and dead in my sin”37 and “Glorious Day” with the lyrics:

I was buried beneath my shame.

Who could carry that kind of weight?

It was my tomb ’til I met You.

I was breathing but not alive.

All my failures I tried to hide.

It was my tomb ’til I met You.38

Both texts communicate a sense of lament over sin; however, the expressed lament is not a present lament over present sin. Instead, the texts convey the lament one previously experienced while in an unregenerated state before placing faith in Christ, or before a certain spiritual “breakthrough.” Furthermore, as one might predict, both songs refer to a past lament in a remarkably brief manner, rapidly progressing towards jubilant celebration. For example, in “Glorious Day,” after less than a minute of reflecting upon a past feeling of lament, the song launches the defining crux of the song, “You called my name – and I ran out of that grave!”

QUESTION 4: DO THE SONGS APPEAL TO

THE SAVING WORK OF CHRIST?

Yes, overwhelmingly so; of the songs, twenty-five of them appeal to the saving work of Christ as payment for sin in some fashion. Phil Wickham and Brian Johnson’s “Living Hope” provides a suitable example with the lyrics, “The God of ages stepped down from heaven to wear my sin and bear my shame. The cross has spoken, I am forgiven.”39 Other songs that reference substitutionary atonement include Hillsong Worship’s “Who You Say I Am” (“While I was a slave to sin, Jesus died for me”)40 and Phil Wickham and Jeremy Riddle’s “This Is Amazing Grace” (“You laid down your life, so I would be set free”).41 While brief, these texts convey how the atonement is the source of forgiveness by which the believer is saved.

In addition, several current songs expand their reference to the atonement to retell the gospel narrative of the death, resurrection, and imminent return of Christ. Songs such as “In Christ Alone” (Townend and Getty), “King of Kings” (Hillsong Worship), and “Man of Sorrows” (Hillsong Worship) each exhibit these lyrical qualities.42 This category of song illustrates a prevalent trend among evangelical worship. Songs that rehearse the gospel narrative play a vital role in evangelicalism by re-centering the worshiper upon the core features of the gospel and thereby the core tenets of Christianity. Furthermore, gospel-narrative songs help the worshiper recount and recall the moment of their conversion. This type of spiritual recollection, Sarah Koenig contends, can function “sacramentally” as a form of eucharistic anamnesis.43 While these songs rightly display a central focus on gospel narrative, the allusions to sin almost entirely reference past sin that has been covered and is no longer an ongoing reality. Thus, with respect to confession, these songs barely qualify to carry an aspect of biblical confession.

QUESTION 5: DO THE SONGS EXPRESS

A RESOLVE TO FLEE FROM SIN?

Somewhat, in the sense that several of these songs express a recommitment to exhibit all-encompassing submission to God’s purposes, which by implication involves living a more pure and sinless life. Only eight songs display this impression in their lyrics, and in doing so the word “sin” is not said outright. Two examples include CityAlight’s “Yet Not I” (“With every breath I long to follow Jesus”)44 and the Gettys’s “In Christ Alone” (“From life’s first cry to final breath Jesus commands my destiny”).45 Maher’s “Lord I Need You” makes a stronger implication of fleeing from sin with the lyric, “Teach my song to rise to you when temptation comes my way. And when I cannot stand, I’ll fall on you.”

The clearest recent example is the song “So Will I (100 Billion X).” This seven-minute composition guides the worshiper through the salvation narrative, beginning at creation and leading toward the Pascal event, with the phrase “so will I” repeated throughout to express the devotion the worshiper will now display in response to comprehending God’s mighty acts of salvation. The climactic moment focusing on the passion of Christ sings,

God of salvation

You chased down my heart

Through all of my failure and pride

On a hill You created

The light of the world

Abandoned in darkness to die

And as You speak

A hundred billion failures disappear

Where You lost Your life so I could find it here

If You left the grave behind You, so will I.46

The word “failure” is used twice and “pride” once, clearly indicating sin. Payment for sin is loosely described, and the lyrics “leaving the grave behind” suggests a commitment to henceforth renounce works of sin and darkness.

ANALYSIS

As the song evaluation illustrates, the current leaning in popular CWM songs shows confession of sin to be notably reduced from a comprehensive model of biblical confession. At best, confession of sin in CWM adopts the impression of being an acknowledgment of previously forgiven sin by recounting the Pascal event, or an expression of spiritual need or weakness. This trend signifies four primary shifts. First, it reveals a departure from gospel-shaped liturgy, where corporate confession of sin is a fundamental aspect of enacting the gospel narrative. Second, the trend suggests a collective avoidance of the subject of sin in worship. Third, it implies a shared view that confession of sin is of peripheral importance to the sanctification of a worshiping community. And last, it overlooks a common scriptural response to God’s self-revelation (Is 6:5; Lk 5:8). Each of these changes is indicative of an overarching ideological move regarding the primary objective of corporate worship. This pervasive change sets the priority of worship to be a subjective experience of intimacy with God above the idea that worship is corporate covenant renewal. The first model of worship seeks to primarily generate a feeling of nearness to God for the worshiper, while the second seeks to retell and enact God’s salvation narrative for the purpose of inscribing gospel truths deep within the worshiper. Two primary sources have contributed to the prevailing ethos of contemporary worship to be subjective intimate experience: the charismatic movement and the church-growth/seeker-sensitive movements.

PRAISE TO WORSHIP: CHARISMATIC INFLUENCE

Contemporary worship finds its roots in Pentecostalism in a convergence of the Jesus People movement of the late-1960s and aspects of the charismatic revival.47 Developments within this confluence include affirmation of outward manifestations of gifts of the Spirit, prolonged periods of singing, and encouragement of physical expressions.48 A key aspect of charismatic influence on contemporary worship is displayed in how intensity is a sought-after goal.49 To the charismatic, to truly worship is to worship with the whole self: body, soul, and spirit and doing so with complete abandon shown through singing, shouting, dancing, clapping, raising hands, kneeling, laying prostrate, and verbal manifestation such as singing and speaking in tongues.50 Therefore, the intent and expectation of worship is to cultivate an “intense intimacy” with God and viscerally encounter His presence.51

In charismatic worship philosophy, intimacy with God is achieved and obtained as the worshiper takes the proper steps in a journey from praise to worship, encouraged through the continuous movement and flow of musical worship. The idea of “praise” and “worship” as two separate ideas runs throughout charismatic theology. Judson Cornwall describes how praise is the beginning of worship, applauding God’s power and shown in outward exuberance, and is an activity of the soul; whereas worship focuses on God’s personhood, and is “God calling to God from within redeemed men” and is an experience of the spirit. “Worship is the end,” Cornwall writes, “all other activities, ceremonies, and ordinances merely serve as a means to that end.”52

In parallel to the imagery of the Jewish tabernacle, praise is what happens in the “outer courts.” Praise emphasizes songs about worship and encountering God as a way of anticipating the experience. As the worshiper progresses into the inner courts and then into the holy of holies, the believer now passes from praise into worship, experiencing the sought-after intimacy with God. Terry Law describes this experience: “You are praising the Lord, you are thanking Him for all He is, when all of a sudden, the words of your mouth move to an attitude of the heart. Love wells up, and adoration comes exploding out of your innermost being.”53 To amplify the general tabernacle imagery behind “praise-and-worship,” the tabernacle furnishings such as the Brazen Altar, the Laver, and the Golden Table also carry meaning for the worship progression. These items signify points of access that having properly adhered to them grant the worshiper closer proximity to the holy of holies.54

A second variation of the worship progression towards intimacy with God is through the five-phase model developed by John Wimber and his community of the Anaheim Vineyard Fellowship.55 These phases begin with invitation: setting the tone and expectation of worship; engagement: praising God for his nature and evolving into more intimate loving language; and exaltation: shown in jubilant physical, vocal, and bodily expressiveness. Exaltation, Wimber explains/claims, “moves to a zenith, a climactic point, not unlike physical lovemaking.” The final phases are adoration: described as a visitation where God’s presence is tangibly felt through the Spirit’s work among the people; and lastly, intimacy: the underlying goal within each phase and according to Wimber, the highest calling of humanity.56

While subjective experience remains paramount in the tabernacle and five-phase models, confession of sin is not intended to be entirely absent. Cornwall and Law both contend that some sort of confession ought to be made in order to draw near to God, represented by the Brazen Altar.57 Similarly, Wimber also affirms the possibility for confession while describing his “engagement” phase in a quasi-covenant renewal sense: “Often this intimacy causes us to meditate, even as we are singing, on our relationship with the Lord. Sometimes we recall vows we have made before our God. God might call to our mind our disharmony or failure in our life, thus confession of sin is involved” (emphasis mine).58 Yet, while a leaning towards confession is present, it is subsumed into the motive of cultivating intimacy with God, not necessarily corporate covenant renewal.

Another charismatic influence on contemporary worship affecting its use of confession is the need for worship experiences to “flow.” If the goal of worship is intimacy with God, then the worship environment needs to nourish and prompt the inward journey of the worshiper through uninterrupted expressions of praise, devotion, and love.59 To achieve flow is to generate a seamless tapestry of song, chorus, prayer, spoken word, and perhaps scripture reading interwoven to create a worship atmosphere that simulates the elapsing of time and facilitates an encounter with God. The intent of worship flow is that the congregation can better experience the eternality of God’s nature, creating a deeper impression of heavenly realities as flow sustains an ambiance of worship with perpetual sight and sound.60 David Blomgren proposes three means in achieving flow. First, flow should move continuously; second, flow should progress logically using the key, tempo, and content of the songs as points of connection; and lastly, flow should progress and compound toward cultivating a climactic experience in worship.61 This heightened expectation to experience the presence of the Lord during a worship set has been said to function sacramentally for the contemporary worshiper. Sarah Koenig contends how in charismatic-evangelical contexts the “praise-and-worship” time of a gathering becomes a vital means through which the congregant experiences a close encounter with God, rather than through the Word and Table.62 Since music carries a sacramental function to mediate the presence of God to the worshiper, other biblically rooted practices like confession and absolution are pushed to the fringes as they are no longer necessary to generate the feeling of God’s immanence. Furthermore, the concept that worship is a journey towards intimacy enabled through free-flowing musical worship has been implanted into the general ethos of evangelical worship due to its adaptation by influential church-growth practitioners.

WORSHIP FOR SEEKERS

Thom Rainer cites five elements of an atmosphere of growing churches as celebrative, friendly, relaxed, positive, and expectant.63 Quality, style, and delivery of music are of paramount importance as the worship gathering is the primary “entry point” for new congregants. Thus, to the churchgrowth practitioner the experience of celebrative engagement cultivated through musical worship becomes a crucial matter. In efforts to create an “experience,” the service needs to flow seamlessly in a well-rehearsed yet ostensibly spontaneous manner. In seeker-sensitive methodology the primary intent of a worship gathering is not to build up the Body of believers but to present an “event” for unchurched non-believers that is accessible, welcoming, entertaining, and informative in order to kindle their curiosity of faith.64

As the seeker movement emerged in the 1980s, pioneering pastors such as Bill Hybels and Rick Warren sought to adopt aspects of charismatic worship into their contexts due to the attractiveness of its celebratory nature, seeming authenticity, and ability to put churchgoers at ease. Former Willow Creek Church worship pastor Joe Horness recounts when Hybels attended a charismatic worship service in 1982 and witnessed “the kind of worship we’ve been dreaming about, worship that was rich and heartfelt, where the presence of God was deep and real, and where hearts were changed as a result of being there.”65 Similarly, Rick Muchow of Saddleback Church attributes the methodological approach adopted by him and Warren to a charismatic worship experience he attended in 1985.66 These and similar occurrences contributed to general charismatic ideas beginning to take shape in the larger milieu of evangelicalism,67 mainly the ideas that God resides in the praises of his people (Ps 22:3) and that music functions sacramentally to gather, mediate, and transform the worshiper through elongated periods of musical worship.68 But supreme to these ideas is the conviction that worship ought to be a celebration.

The concept of celebratory worship is deeply imbedded within church-growth philosophy. C. Peter Wagner, the pioneer of third-wave charismaticism and heavily influenced by John Wimber’s theology and methods,69 speaks to this assumption. He describes the unique experience of the gathered Body, who have come expectant and hungry to encounter God, and when people gather under these conditions, a special, celebratory worship experience occurs.70 Moreover, for a local church to grow, it is vital that worship gatherings are exciting, engaging, and celebratory as it is a sign that the people are earnest and the power of God is potently near. Wagner argues that celebration and festival are prominent activities for God’s people, appealing to biblical history, citing the centrality of the Temple and yearly festivals within Israel’s worship, and to church history, citing camp meetings, Finney’s revivals, and Billy Graham crusades.71 The prevailing philosophy is that churchgoers will not be motivated or attracted to worship if it is somber, reserved, and “no fun.”72 Following Wagner’s thinking, confession can easily be relocated as a fringe priority. For the congregation to pause and directly confess sin would disrupt the flow and sense of jubilancy, a clear aim of celebratory worship.

Celebratory worship as a means to promote church growth runs in tandem with a driving ambition of seeker-sensitive worship of eliminating any barriers that could repel or confuse a seeker. Early practitioners of seeker-sensitive worship thus employed guiding principles such as informality of style, dress, and décor, and an overall casual atmosphere. Moreover, they emphasized relevancy of content, using the textual and musical language of the demographic, visual appeal, and a low-pressure environment regarding participation.73 Overarching each of these principles is the desire to be relevant to the contemporary needs of the participant.74 Thus liturgical content is less concerned with conveying theological and biblical substance, and more set on speaking to the immediate emotional or practical needs of the congregant. The presumptive result is that to the seeker, God will appear more immanent and intimate, conveying a faith that pragmatically “works” and is authentic about the struggles of everyday life.75 Since contemporaneity is of high concern in seeker-sensitive worship, ancient practices are then irrelevant, confession of sin being no exception.

Pastor and writer Timothy Wright explains, “Irreligious people do not necessarily perceive sin as their problem. The rite of confession and absolution can come across to them as condemning. If not done with their needs and perceptions in mind, confession and absolution will alienate visitors.”76 This is not to obliterate mention of sin in a worship setting, but instead of overtly confronting sin in confession, sin is addressed by first relating to the need of the congregant and to later introduce the source of the need (sin). The solution for Wright is to intersperse and embed confession throughout the service with warmer colloquial language through a variety of opportunities, such as informal prayer, songs that could mention weakness and need, or moments of silence.77 While confession is loosely recognized, its adaptation to suit a seeker-sensitive context subverts its crucial function. The Bible portrays confession as coming face-to-face with our sin that raises challenging questions and unsettling truths about ourselves, which are then met with an assurance of pardon.78 The seeker sensitive solution to make confession seem more palatable confines it to the periphery, but within that limitation it cannot achieve the full scope of its implications.

CONCLUSION

This discussion has argued that confession of sin in CWM has been reduced to a reflective notion rather than a present action. Biblical confession throughout Scripture contains open acknowledgement of sin, lament over sin, and a resolve to flee from sin. Confession of sin is a God-centered activity that expresses full dependency on God’s grace and mercy for life and salvation. Ultimately, confession of sin plays a vital function in the regular covenant renewal that gospel-shaped liturgy enacts in how it reinstates the redeemed Body as recipients of a God-initiated covenant through the atonement and baptism in the Spirit.

The data presented in the song evaluation of CWM indicates weak adherence to the parameters of biblical confession. This finding is in part due to elevating the idea of worship as subjective intimate experience above the concept of worship as corporate covenant renewal. This evolution stems from two streams of Christian thought. The first is the charismatic movement, which promotes that the goal of liturgy is to cultivate intimacy with God by passing from praise to worship. While confession can be part of the worship journey, it is subsumed into the motive of achieving intimacy with God. The second stream is the church-growth and subsequent seeker-sensitive movements that promote the need for celebratory, dynamic, and relevant worship experiences that will attract, relax, and retain the congregant. Thus, the counterintuitive nature of confession and its disquieting implications appear in conflict with generating an appealing “event” for seekers.79 Confession may still be integrated into the “flow” of seeker-sensitive worship experiences but is reduced to maintain a palatable quality for the congregant.

While this discussion contends that gospel-shaped liturgy that includes habitual confession of sin provides ample opportunity for the worshiping community to grow in sanctification, it is not to presume that some of the aforementioned aspects of charismatic and seeker-sensitive worship are inherently discordant with gospel-shaped liturgy. For example, worship is in part an inward journey of the worshiper towards intimacy, worship should be a celebration of the gospel, and corporate gatherings ought to be hospitable to seekers and be mindful of their perspective. Moreover, a worshiping community should embrace gospel-shaped liturgy while maintaining a sense of “flow” in which its contents unfold in a logical and progressive manner displaying preparation and thorough forethought.80 However, each of these concerns in and of themselves cannot embody the full scope of biblical worship. Worship is more than an individual subjective experience, or an “entry point” for seekers, and crafting “the perfect worship set” is not the end goal of liturgy. Rather, these facets of a worship gathering ought to be considered as merely components within the overarching motive of renewal in the new covenant set forth in Christ.

Appendix: Analysis of CCLI Top 100 Worship Songs referencing

an Aspect of Biblical Confession of Sin

2. See Robert Webber, Planning Blended Worship: The Creative Mixture of Old and New (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1998), 41.

3. Swee Hong Lim and Lester Ruth, Lovin’ on Jesus: A Concise History of Contemporary Worship (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2017), 95.

4. CCLI Top 100 Worship Songs, https://songselect.ccli.com/Search/Results?List=top100, accessed January 2021

5. Richard C. Leonard, “Confession of Sin,” in The Biblical Foundations of Christian Worship, ed. Robert Webber, 8 vols., The Complete Library of Christian Worship (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1993), 1:304–6.

6. Bryan Chapell, Christ-Centered Worship: Letting the Gospel Shape Our Practice (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2017), 88.

7. Leonard, “Confession of Sin,” 305.

8. Leonard, “Confession of Sin,” 305.

9. Leonard, “Confession of Sin,” 306.

10. Chapell, Christ-Centered Worship, 183.

11. Chapell, Christ-Centered Worship, 88.

12. See Robbie F. Castleman, Story-Shaped Worship: Following Patterns from the Bible and History (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2016); Mike Cosper, Rhythms of Grace: How the Church’s Worship Tells the Story of the Gospel (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2013); Bryan Chapell, Christ Centered Worship; James K. A. Smith, You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit (Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2016).

13. See Constance M. Cherry, The Worship Architect: A Blueprint for Designing Culturally Relevant and Biblically Faithful Services (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2010). In this work, Cherry contends for the gospel-shaped, or four-fold order, while maintaining worship is a divine-human dialogue of revelation and response.

14. Andrew E. Hill, “Biblical Foundations of Christian Worship,” in Worship and Mission for the Global Church: An Ethnodoxology Handbook, ed. James R. Krabill et al. (Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 2013), 6.

15. See Smith, You Are What You Love, 22.

16. Castleman, Story-Shaped Worship, 83.

17. Emily Brink and John D. Witvliet, eds., The Worship Sourcebook, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2013). This resource provides several rich and relevant examples, models, and texts.

18. William A. Dyrness, “Confession and Assurance,” in A More Profound Alleluia: Theology and Worship in Harmony, ed. Leanne Van Dyk (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005), 32.

19. Dyrness, “Confession and Assurance,”” 47.

20. Smith, You Are What You Love, 94

21. The Episcopal Church, The Book of Common Prayer (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 79.

22. Lim and Ruth, Lovin’ on Jesus, 9.

23. This study is put forth with the cognizance that utilizing data available from CCLI is merely one way to gauge the prevalence of certain trends in the Church. There are other ways to gain insight, such as radio plays, YouTube views, surveys, and other forms of empirical data. However, since CCLI is a widely used resource among most churches, it is a fitting starting point for gathering a picture of influential trends.

24. See the appendix for a table identifying which of the songs relate to confession and how they do so.

25. Cody Carnes, Run to the Father, Run to the Father (Nashville: Sparrow Records, 2020).

26. Matt Redman, The Heart of Worship, Intimacy (East Sussex, UK: Survivor Records, 1998).

27. Cody Carnes, Nothing Else, Run to the Father (Nashville: Sparrow Records, 2020).

28. Elevation Worship, O Come to the Altar, Here as in Heaven (Franklin, TN: Essential Worship, 2015).

29. We The Kingdom, God So Loved, Holy Water (Nashville: Sparrow Records, 2020).

30. Passion, Way Maker, Roar (Atlanta: sixstepsrecords, 2020).

31. Elevation Worship, Graves into Gardens, Graves into Gardens (Charlotte, NC: Elevation Worship, 2020).

32. Matt Boswell and Matt Papa, His Mercy Is More, His Mercy Is More: The Hymns of Matt Boswell and Matt Papa (Nashville: Getty Music, 2019).

33. A few of the references are Jeremiah 31:34, Micah 7:18-20, Romans 3:21-26, and 1 John 3:1

34. Andrew Peterson, Is He Worthy?, Resurrection Letters: Volume One (Nashville: Centricity Music, 2018).

35. Vertical Worship, Yes I Will, Bold Faith Bright Future (Franklin, TN: Essential Worship, 2018).

36. Elevation Worship, Here Again, Hallelujah Here Below (Charlotte, NC: Elevation Worship, 2018).

37. North Point Worship, Death Was Arrested, Nothing Ordinary (Nashville: Centricity Music, 2017).

38. Passion, Glorious Day, Worthy of Your Name (Atlanta: sixstepsrecords, 2017).

39. Phil Wickham, Living Hope, Living Hope (Hollywood: Capitol Records, 2018).

40. Hillsong Worship, Who You Say I Am, There Is More (Sydney: Hillsong Music, 2018).

41. Phil Wickham, This Is Amazing Grace, The Ascension (Brentwood, TN: INO Records, 2013).

42. While not in the top 100 songs on CCLI, Matt Boswell and Matt Papa’s “Come Behold the Wondrous Mystery” is, in the humble opinion of this author, the strongest current song of this nature.

43. Sarah Koenig, “This Is My Daily Bread: Toward a Sacramental Theology of Evangelical Praise and Worship,” Worship 82, no. 2 (2008): 152.

44. CityAlight, Yet Not I but through Christ in Me, Yet Not I (Colorado Springs, CO: Integrity Music, 2018).

45. Keith Getty and Kristyn Getty, In Christ Alone, In Christ Alone (Nashville: Getty Music, 2006).

46. Hillsong United, So Will I (100 Billion X), Wonder (Sydney: Hillsong Music, 2017).

47. Don Williams, “Charismatic Worship,” in Exploring the Worship Spectrum: Six Views, ed. Paul A. Basden and Paul E. Engle (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2004), 139.

48. Lim and Ruth, Lovin’ on Jesus, 17.

49. Lim and Ruth, Lovin’ on Jesus, 18.

50. Frank Macchia, “Signs of Grace: Towards a Charismatic Theology of Worship,” in Towards a Pentecostal Theology of Worship, ed. Lee Roy Brown (Cleveland, TN: CPT Press, 2016), 153–55.

51. Terry Law, How to Enter the Presence of God: You’ve Always Yearned To—Now Here’s How! (Tulsa, OK: Victory House, 1994), 152.

52. Judson Cornwall, Let Us Worship (Alachua, FL: Bridge-Logos Publishers, 2013), 148.

53. Law, How to Enter the Presence of God, 149.

54. See Barry Liesch, People in the Presence of God (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1988); Judson Cornwall, Let Us Draw Near (Plainfield, NJ: Bridge Logos Foundation, 1977); Law, How to Enter the Presence of God.

55. See Andy Park, Lester Ruth, and Cindy Rethmeier, Worshiping with the Anaheim Vineyard: The Emergence of Contemporary Worship (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2016).

56. John Wimber, The Way In Is the Way On, ed. Christy Wimber (Boise, ID: Ampelon Publishing, 2006), 121–24.

57. Law, How to Enter the Presence of God, 16–17; Cornwall, Let Us Draw Near, 48.

58. John Wimber and Carol Wimber, “Why We Worship and the Phases of Worship,” December 12, 2012, http://www.thevineyardfw.org/wordpress/why-we-worship-the-phases-of-worship-by-john-wimber/.

59. Koenig, “This Is My Daily Bread,” 143.

60. Zachary Barnes, “How Flow Became the Thing,” in Flow: The Ancient Way to Do Contemporary Worship, ed. Lester Ruth (Nashville: Abingdon, 2020), 21.

61. David K. Blomgren, Song of the Lord (Portland, OR: Bible Temple Publishing, 1989), 29–31.

62. Koenig, “This Is My Daily Bread,” 143, 147.

63. Thom S. Rainer, The Book of Church Growth (Nashville: B&H Academic, 1998), 228.

64. Smith, You Are What You Love, 103.

65. Joe Horness, “Contemporary Music-Driven Worship,” in Exploring the Worship Spectrum: Six Views, ed. Paul A. Basden (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2004), 108.

66. Lim and Ruth, Lovin’ on Jesus, 34.

67. Larry Eskridge, God’s Forever Family: The Jesus People Movement in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 275

68. Barnes, “How Flow Became the Thing,” 17. For a critical evaluation of the meaning of Psalm 22:3, see Matthew Sikes, “Does God Inhabit the Praises of His People? An Examination of Psalm 22:3,” Artistic Theologian 8 (2020): 5–22.

69. See C. Peter Wagner, The Third Wave of the Holy Spirit: Encountering the Power of Signs and Wonders Today (Ann Arbor, MI: Servant Publishing, 1988). Wagner describes his experience and influence from Wimber in chapter one, “How I Learned about the Power.”

70. C. Peter Wagner, Your Church Can Grow (Glendale, CA: Regal Books, 1976), 97.

71. Wagner, Your Church Can Grow, 98.

72. Wagner, Your Church Can Grow, 98.

73. Edward G. Dobson, Starting a Seeker-Sensitive Service (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1993), 23.

74. Lim and Ruth, Lovin’ on Jesus, 2–3

75. Timothy K. Wright, A Community of Joy: How to Create Contemporary Worship (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1994), 25.

76. Wright, A Community of Joy, 125.

77. Wright, A Community of Joy, 125.

78. Smith, You Are What You Love, 104.

79. Smith, You Are What You Love, 105.

80. Lester Ruth, “Beatific Flow: Overarching Guidelines,” in Flow: The Ancient Way to Do Contemporary Worship (Nashville: Abingdon, 2020), 91–93.