Thomas Hastings and the First American Sacred Cantata

Artistic Theologian 11 (2024): 41-53

David W. Music is professor emeritus of church music at Baylor University, where he taught from 2002 to 2020.

The tradition of American Protestant church choirs performing lengthy choral works at Christmas, Easter, and other times of the year is one that was almost taken for granted until recently.2 These works, often labeled “oratorio,” “cantata,” “musical,” or some other designation, were intended to give heightened emphasis to a particular season, celebration, or event; serve as a challenge to the choir; provide an outreach opportunity into the community; or all of these simultaneously. The compositions thus offered ranged from classic oratorios by Europeans such as Bach, Handel, Mendelssohn, and Brahms to functional works written by U.S. composers that were designed specifically for the church choir of modest means and abilities.

In 1986, Thurston J. Dox published American Oratorios and Cantatas, a bibliography of major vocal works by American composers from colonial times to 1985.3 This comprehensive catalog lists more than 3,000 published and unpublished items that were designated “cantatas” by their composers or by others. Dox’s bibliography is a masterful achievement that has deservedly become a standard resource in the field of American choral music.

One piece that does not appear in the bibliography, or—to my knowledge—in any other discussion of American cantatas, is a work by Thomas Hastings titled The Christian Sabbath: A Sacred Cantata, which may very well be the earliest published American religious piece to bear the designation “cantata.” Hastings (1784–1872) and his sometime collaborator and rival, Lowell Mason (1792–1872), were the chief figures in the reform of American church music during the first half of the nineteenth century, Hastings mainly in New York and Mason in Massachusetts. Both were prolific composers and compilers of tune books, but Hastings also achieved prominence as an author of philosophical writings on church music, including the books Dissertation on Musical Taste (1822, rev. ed. 1853), The History of Forty Choirs (1854), and Sacred Praise (1856), as well as numerous articles in two newspapers he edited, the Western Recorder (1824ff) and The Musical Magazine (1835ff).4 Hastings is remembered today primarily as the composer of three popular hymn tunes: Toplady (“Rock of Ages, cleft for me”), Ortonville (“Majestic sweetness sits enthroned”), and Zion (“On the mountain’s top appearing”), but he also published many other hymn tunes, as well as anthems and service music.5

PUBLICATION OF THE CHRISTIAN SABBATH

The Christian Sabbath was first printed in the late fall or winter of 1816, when it appeared in an appendix to the second edition of Hastings’s tune book Musica Sacra, as well as in a separate pamphlet titled Christian Sabbath and Nativity Anthem; Together with a Few Other Pieces of Sacred Music.6 Both items were advertised in the Utica (New York) Patriot and Patrol for December 10, 1816:

SEWARD & WILLIAMS, No. 60, Genessee street [sic], Have just published, and now offer for sale, wholesale and retail, the second edition of the MUSICA SACRA. This collection of Church Music having been introduced into general use in this part of the country its merits are too well known to need any recommendation. Owing to the great haste in which the first edition was printed, a few typographical errors occurred which have been carefully corrected in the present impression.

Also, a few copies of The Christian Sabbath, a Sacred Cantata: together with a few other pieces of Sacred Music not before published. Price 25 cents.

Dec. 10, 1816.

Musica Sacra was originally issued in the form of two shorter publications that were combined to form the first complete edition as it is known today, at which time an appendix containing mainly chants for the Episcopal church was added (Shaw-Shoemaker no. 35384). Though dated 1815 on both the title page and the copyright notice, this first (combined) edition was probably not issued in its present form until well into 1816.7 The second edition of Musica Sacra, published later that year, included an additional appendix, and it was here that The Christian Sabbath appeared, along with the anthem Nativity (“Behold, I bring you glad tidings”) and the hymn tunes Portsea and Pressburgh.

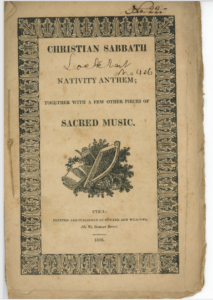

Three copies of the pamphlet containing The Christian Sabbath are held by Bowld Music Library at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary (see fig. 1). Each of these contains the same four items as the second appendix in Musica Sacra, using an identical order and pagination. Composer attributions are not found with any of the pieces in either the appendix or the pamphlet, but both Nativity and Portsea were later issued many times under Hastings’s name, and the other two pieces, The Christian Sabbath and Pressburgh, are almost certainly also of his composition.8

FIG. 1. CHRISTIAN SABBATH AND NATIVITY ANTHEM (UTICA, NY: SEWARD AND WILLIAMS, 1816) (BOWLD MUSIC LIBRARY, SOUTHWESTERN BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY).

The pamphlet and the second appendix in Musica Sacra have the same musical content and appear to have been printed from the same plates. Since the advertisement notes that only “a few copies” of the pamphlet are available (suggesting that it was almost sold out), while the new edition of Musica Sacra was “just published,” it might be assumed that the pamphlet was issued before the second edition of the tune book, which subsequently incorporated its contents as an appendix. This suggestion seems to be supported by the claim in the advertisement that the pamphlet contains “pieces of Sacred Music not before published,” which would not be quite true if they had appeared previously in the appendix to Musica Sacra.

However, it seems more likely that the pamphlet was published almost (if not indeed) simultaneously with the new edition of Musica Sacra. The purpose of the pamphlet was undoubtedly to provide persons who had purchased the first edition of the tune book with the additional material found in the second edition so they would not have to buy an entirely new book. A simultaneously issued version of the pamphlet would clarify the phrase “pieces of Sacred Music not before published” in the advertisement. It is also possible that “not before published” was intended simply to convey that the pieces were new and not available outside Hastings’s tune book and the pamphlet. That there were only “a few copies of the pamphlet” probably indicates that not many were printed rather than that they were nearly sold out.

There are also indications that two versions of the pamphlet were published, one that was probably issued at about the same time as the second edition of Musica Sacra, and the other appearing later in an amended printing: the versions of The Christian Sabbath in Musica Sacra and one of the extant pamphlets contain several misprints that have been corrected in the other two extant pamphlets (plus one located at Andover Newton Theological School). For example, in Musica Sacra and its corresponding pamphlet, the last note on page 3, measure 8, in the first soprano appears incorrectly as an F5, changed to a G5 in the corrected pamphlets. Even more telling is the last measure of page 7: Musica Sacra and the parallel pamphlet contain an obvious mistake on the second note of both soprano parts (first soprano, F4; second soprano, D4); this was corrected in the other known pamphlets but evidence of the change is clearly visible (fig. 2).9

FIG. 2. THE CHRISTIAN SABBATH (PAMPHLET VERSION), SOPRANO DUET (WITH INSTRUMENTAL BASS), P. 7, LAST M.

Thus, copies of the pamphlet and the second edition appendix of Musica Sacra were published simultaneously (or nearly so), after which a revision of the pamphlet was issued. How widely the pamphlet might have been distributed is not certain, but it is known that twelve copies were presented to the Andover Musical Association in February of 1817, perhaps to supplement copies of the first edition of Musica Sacra that they already owned.10

THE CHRISTIAN SABBATH

The text of The Christian Sabbath is that of a four-stanza hymn by Isaac Watts that was originally published in his Hymns and Spiritual Songs (1707) as “Welcome Sweet Day of Rest,” although the opening line appeared in Hastings’s cantata as “Welcome, thou day of rest.” In addition to the change in the first line, several other modifications were made in the words, the most radical of which was the replacing of Watts’s “And sit and sing herself away” in stanza four with a completely new line, “till it be call’d to soar away.” These changes in the text were the work of the American Congregationalist minister and historian Jeremy Belknap, who, in his Sacred Poetry of 1795, sought to expunge from the hymns of Watts (and others) “epithets and allusions taken from ‘mortal beauties,’ and applied to the Saviour.”11 Belknap’s prefatory statement explains his change of “sweet” to “thou” and the replacement of “sing herself away”: both alterations were intended to lessen the amatory implications of Watts’s text.

Hastings’s music is composed for a bass and two soprano soloists, four-part choir (SSTB), and an instrumental bass. The instrumental bass is unfigured; no separate part is provided during the choral sections, where the instrument probably doubles the vocal bass and provides supporting harmonies in continuo fashion. Structurally, the work is divided into five sections, an opening choral movement (mm. 1–100, pastorale), followed by a bass solo (101–49), a soprano duet (149–211), and two more choral sections (212–32, adagio; 233–303, con spirito).

Melodically, harmonically, and rhythmically, the work is relatively uncomplicated, in keeping with Hastings’s reform emphasis on accessibility and verbal clarity.12 In the choral sections, the writing is mainly homophonic, with some grouping of voices (SS-TB, for example) and a few very brief imitative or pseudo-imitative passages (ex. 1; see also mm. 233–38).

EX. 1. THE CHRISTIAN SABBATH, MM. 35–37. INSTRUMENTAL BASS OMITTED (DOUBLES VOCAL BASS).

The soprano duet section is almost exclusively in parallel thirds (ex. 2).

EX. 2. THE CHRISTIAN SABBATH, MM. 199–206.

The score calls for tenors who can sing high B-flats (mm. 85, 246)—though an optional lower octave is provided for the first instance—and second sopranos who can negotiate a range from B♭₃ to G₅. All the voice parts are characterized by relatively high tessituras.

Admittedly, the music Hastings composed has some serious weaknesses. One of the principal drawbacks is its over-repetition of text. For example, it takes fifty-nine measures at a pastorale tempo to set the ten words “Welcome, thou day of rest / that saw the Lord arise.” These textual phrases are not important enough to bear the weight of so much repetition, especially without some sort of significant key or tempo change, dynamic gradation, or melismatic or contrapuntal writing—and given Hastings’s philosophy of church music, not many instances of melismatic or imitative writing would be expected.13 The bass solo is rather formless, the melody part having little discernible sense of direction despite a few repeated phrases and sequential passages. The over-emphasis on parallel thirds in the soprano duet becomes tiresome, a situation that is exacerbated by a repetition of its opening section. The last (choral) section has some effective Handel-like passages pitting long note themes against others in shorter note values (ex. 3), but there are also too many stops and starts in the music.

EX. 3. THE CHRISTIAN SABBATH, MM. 252–57. INSTRUMENTAL BASS OMITTED (DOUBLES VOCAL BASS).

The range of modulation throughout the work is small (the key signature never leaves E-flat major), and there are few efforts at textual expression. At the same time, the range and tessitura of some of the voice parts would present challenges for an amateur choir. Overall, the simplicity and clarity for which Hastings sought is simply not well suited to sustain interest in a lengthy work. The composer perhaps did not have the experience necessary to write a piece of this sort at this time in his life, especially considering that this is one of his early compositions.

THE DESIGNATION “CANTATA”

Perhaps the most interesting feature of Hastings’s work is his identification of it as a “cantata.” No other composition by an American to use this specific label has been discovered before Hastings’s work. Generally speaking, through-composed settings of poetic texts from this period of American music are called anthems or (more properly) set pieces rather than cantatas.14 Thus, it might well be asked why the composer gave this work the latter designation.

Unfortunately, Hastings himself does not appear ever to have defined the word “cantata,” despite writing several books and numerous newspaper columns on music, especially sacred music. Therefore, we must look to the work itself to determine why the composer gave it this name.

One factor that sets this composition apart from a typical set piece of the time is its length: at 303 measures (not counting repeats), The Christian Sabbath is about three times longer than the average contemporaneous American anthem or set piece. To be sure, a few contemporaneous anthems by U. S. composers are actually longer than Hastings’s work—for example, Daniel Merrill’s “O come, let us sing unto the Lord,” which registers 399 measures—but the expansive nature of the piece must certainly have been a factor in his choosing to call it a “cantata.”15

Another feature that sets The Christian Sabbath apart from many other American choral works of the time is the presence of an independent instrumental bass, particularly during the solo and duet passages. Autonomous instrumental parts are found in some earlier and contemporaneous anthems—including Hastings’s own Nativity, the piece that follows The Christian Sabbath in the tune book appendix and the pamphlet—but this characteristic might also have played a part in the use of the term cantata.

A further component of The Christian Sabbath that is somewhat unusual for the time is that the solo and duet passages are obviously designed for performance by single voices with instrumental accompaniment. The solo passages that appear in anthems and set pieces by earlier American composers were generally intended either for the entire voice section or a small group, not an individual singer, and they only very occasionally featured an independent instrumental part. To be sure, some of Hastings’s own anthems—including Nativity—contain true solos with accompaniment, so again this feature cannot have been the principal criterion for his choice of the term.

Another critical feature of the work is its strongly sectional character. There is a firm division between movements that was a bit unusual in earlier American sacred music, but here again the same characteristic is found in Hastings’s Nativity, which is clearly labeled “an Anthem.”

It was likely not any one of these factors, but their combination that led Hastings to label his work a “cantata”: it is a longer-than-average non-dramatic work that features an independent instrumental part, and self-contained vocal solos and choral sections. Today we might consider this work to be simply an over-sized set piece, but Hastings apparently felt that such a designation was not appropriate for this work and that it was better suited to be labeled a “cantata.”

That said, Hastings’s use of the term is still puzzling. What model was he following in employing this label? Eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century usage of the term “cantata” in Europe, England, and America usually indicated a secular work.16 It is doubtful that Hastings knew any of the German church compositions that are now called “cantatas,” such as those by Bach or Telemann; at any rate, works like these were seldom known by that description during his time.17

A year after publication of The Christian Sabbath, the New-York Daily Advertiser announced a “Grand Oratorio” to be presented by the New York Handel and Haydn Society. The “Oratorio” was to include a “New Sacred Cantata . . . composed and to be sung by Mr. [Thomas] Phillipps”; the cantata evidently consisted of only two items, a recitative and an aria.18 While the advertisement shows that others besides Hastings were using this classification for sacred vocal works, such designations appear to have been rare during the time Hastings composed and published The Christian Sabbath, particularly in the United States. For the present, the question of what model Hastings might have followed (if any) in using the term must remain unanswered.

While The Christian Sabbath was perhaps the first American sacred composition actually to be labeled a “cantata,” it was certainly not the first religious cantata-like piece written in the New World. Other previously composed works that approach the form and dimensions of the cantata as the term is usually understood include William Selby’s “Anthem for Christmas” (“The heav’ns declare thy glory, Lord”); Hans Gram’s “Bind Kings with Chains” (labeled “An occasional anthem”); and Oliver Holden’s “A Dirge, or Sepulchral Service Commemorating the Sublime Virtues and Distinguished Talents of General George Washington,” first performed and published in 1800 in honor of the recently deceased president.19 Since its subject matter consisted principally of recounting Washington’s virtues, the “Dirge” might well be thought of as a secular work, though one movement is essentially a prayer to God and another references a passage from the Episcopal burial service.

Another sacred piece with cantata-like dimensions and format was Der 103te Psalm by the Moravian composer David Mortiz Michael for alto, tenor, and bass soloists; choir; and orchestra. While this work more nearly resembles a cantata as the term is currently used than Hastings’s more modest piece, Michael did not use that classification for it (he labeled it merely a Gesang), and there is little likelihood that the New York composer knew Michael’s work, which did not achieve publication until 2008.20

Finally, mention must be made of Samuel Felsted’s Jonah, an “oratorio” that was published in London in 1775 and performed several times in the United States during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Felsted was a native of Jamaica and served as organist there at St. Andrew Parish Church.21 In dimensions, Jonah is more like a cantata than an oratorio (it contains only twelve movements), though its dramatic form makes the “oratorio” designation that Felsted gave it suitable.

Although these and similar cantata-like works all preceded Hastings’s The Christian Sabbath, none of them was actually called a cantata. It is quite possible that Hastings was the first American composer to use this term as a label for one of his sacred works.

SUBSEQUENT HISTORY OF THE CHRISTIAN SABBATH

The Christian Sabbath was not reprinted in the 1818 edition of Musica Sacra, a combination of Hastings’s tune book with Solomon Warriner’s Springfield Collection of 1813, or any of the editions that followed. In fact, after its two 1816 printings, it does not seem to have received publication by Hastings or anyone else during the nineteenth century, nor have any performances of it been noted.

This silence probably resulted at least in part from the anomalous position of the work. Unlike an anthem or set piece, a cantata could fill no specific liturgical position in an American Protestant church of the early nineteenth century: it was much too long for performance in a normal worship service, called upon resources that many congregations probably could not muster, and the text made it unlikely that it would be appropriate for such special occasions as the dedication of a new church building or the installation of a minister. It might have found a home in the concerts of sacred music that were sometimes held in the early nineteenth century (like the one that featured Phillipps’s “new sacred cantata”), but no such usage for Hastings’s work has come to light. It would probably be a rare singing school that would give The Christian Sabbath the time and energy required for rehearsing and/or performing it. On the other hand, the piece was probably too short and undistinctive to appeal to groups that were beginning to explore the oratorio repertory, such as the Handel and Haydn Societies of Boston or New York.22 In other words, it was just about the wrong length and scope for practical use, and these features, combined with its minimal harmonic and rhythmic interest, make it little wonder that the work apparently achieved few—if any—performances.

It is perhaps telling that in his subsequent prolific output Hastings used the term “cantata” for only one other piece, Story of the Cross: a new cantata for Sunday-school concerts, published in 1867, more than fifty years after The Christian Sabbath. This was a joint effort between Hastings and Philip Phillips (1834–1895), a renowned gospel singer of the time. The exact role of each man in this work is not certain since attributions are not found on the individual pieces. Hastings is named first on the title page and initial page of music, but Phillips copyrighted the work, signed the preface, and provided outlines of some of his sacred concert programs at the end. It is likely that Phillips was the driving force behind the project and perhaps wrote or compiled the text and some of the songs. Hastings’s role was probably as a composer or arranger of some of the items. Story of the Cross is a much more conventional example of a cantata than The Christian Sabbath by virtue of its greater length, semi-narrative textual approach, and certain musical features, particularly the notated keyboard introductions, interludes, and solo accompaniments. The presence of two Anglican chant-style sections is also noteworthy. By the time of Story of the Cross, of course, American composers were writing both sacred and secular cantatas by the score.

CONCLUSION

Many questions still surround The Christian Sabbath. What was Hastings’s motivation for writing the work? Why did he label it a “cantata”? What model did he follow, if any? Why did he not compose more works in this vein? Did it receive any actual performances? While answers to these questions are not readily available, and though our interest in The Christian Sabbath may be principally historical rather than as a piece for practical performance, it can at least be said that this appears to have been one of—if not the—first uses of the term “cantata” to describe a piece of sacred music by an American composer. For that reason, if for no other, Hastings’s cantata deserves to be remembered.

2. The replacement of church choirs with contemporary worship ensembles has often led to the abandonment not only of Sunday-by-Sunday choral music but also the absence of major choral works in many American churches.

3. Thurston J. Dox, American Oratorios and Cantatas: A Catalog of Works Written in the United States from Colonial Times to 1985, 2 vols. (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1986).

4. See John Mark Jordan, “Sacred Praise: Thomas Hastings and the Reform of Sacred Music in Nineteenth-Century America” (PhD diss., Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1999), for a comprehensive discussion of Hastings’s writings on church music. Other important studies of Hastings and his music are Mary Browning Scanlon, “Thomas Hastings,” The Musical Quarterly 32, no. 2 (April 1946), 265–77; James E. Dooley, “Thomas Hastings: American Church Musician” (PhD diss., Florida State University, 1963); and Hermine Weigel Williams, Thomas Hastings: An Introduction to His Life and Music (New York: iUniverse, 2005).

5. The named texts are the ones with which Hastings first published the tunes. Other texts have been used with each of these melodies.

6. Musica Sacra: a collection of psalm tunes, hymns and set pieces, 2nd ed., rev. and corr. (Utica, NY: Seward & Williams, 1816); Christian Sabbath and Nativity Anthem; Together with a Few Other Pieces of Sacred Music (Utica, NY: Seward and Williams, 1816).

7. See my introduction to Thomas Hastings: Anthems, Recent Researches in American Music 83 (Middleton, WI: A-R Editions, 2017), viii, for a discussion of the somewhat confusing publication history of the first edition. It appears that when the two pamphlets were combined in 1816 to make up the first complete edition of the tune book, Hastings simply reused the title page from the first pamphlet, which probably appeared in late 1815.

8. Hastings apparently never published The Christian Sabbath and Pressburgh again after their appearances in the appendix to the second edition of Musica Sacra and the pamphlet.

9. I am grateful to Allen Lott for pointing out the Southwestern Seminary copies of the pamphlets to me and providing me with relevant material from them.

10. Williams, Thomas Hastings, 20.

11. Jeremy Belknap, Sacred Poetry. Consisting of psalms and hymns, adapted to Christian devotion, in public and private (Boston: Apollo Press, 1795), preface; Watts’s hymn appears on pp. 282–83. In Sacred Poetry, the new line in stanza 4 reads “Till it is call’d to soar away.”

12. See the section “Of Fugue and Imitation” in Thomas Hastings, Dissertation on Musical Taste, rev. ed. (New York: Mason Brothers, 1853), 149–53.

13. For example, in Hastings’s opinion, fugues in vocal music of the past have “done extensive injury, by the confusion of words they have occasioned” (“Different Departments of Music. No. XV,” Western Recorder, October 24, 1826).

14. Settings of prose texts are generally called “anthems,” while through-composed settings of poetry are “set pieces.”

15. Karl Kroeger, ed., Early American Anthems. Part I: Anthems for Public Celebrations, Recent Researches in American Music 36 (Madison, WI: A-R Editions, 2000), xiii; Merrill’s anthem appears on pp. 31–58. Kroeger’s introduction provides a useful summary of the typical features to be found in American anthems of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

16. For examples of some of these secular works, see under “cantata” in the indexes of O. G. Sonneck, A Bibliography of Early Secular American Music (Washington, DC: H. L. McQueen, 1905; rev. and enl. by William Treat Upton, New York: Da Capo Press, 1964), and Richard J. Wolfe, Early Secular Music in America, 1801–1825: A Bibliography (New York: New York Public Library, 1964). See O. G. Sonneck, Early Concert-Life in America (1731–1800) (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1907; reprint, New York: Da Capo Press, 1978), for newspaper reports of cantata performances in eighteenth-century America.

17. On page x of American Oratorios and Cantatas, Dox observed that “in the eighteenth century, the term ‘cantata’ was applied to accompanied works for soloists, with vocal ensembles or chorus. Both sacred and secular texts were used.” However, the specific designation “cantata” for a piece of sacred music appears to have been relatively uncommon and was certainly rare in early America. The pre-1816 American sacred pieces listed in Dox’s bibliography either were not called cantatas by their composers or (as far as can be discovered) by their contemporaries, or their dates of composition and/or performance are not known.

18. New-York Daily Advertiser (December 15, 1817). The term “oratorio” was often used in early nineteenth-century America to indicate a miscellaneous concert, not necessarily a single major work (such as an oratorio by Handel). The recitative-aria pair by Phillipps was listed in the advertisement as “And have I never praised the Lord” and “Praise the Lord,” respectively. The Orange County Patriot of November 18, 1817, reported that Thomas Phillipps had “recently arrived in New-York from Europe.”

19. The Heav’ns Declare” was printed in Selby’s serialized publication Apollo and the Muses (1791), and Gram’s “Bind Kings with Chains” appeared in Laus Deo! The Worcester Collection of Sacred Harmony, 5th ed. (1794). For a description of Selby’s piece, see Nicholas Temperley, Bound for America: Three British Composers (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003), 38–40. An unusual feature of “Bind Kings with Chains” is the presence of a “Largo Recitativo” for bass soloist and an instrumental bass. The “Dirge, or Sepulchral Service” was published anonymously in Boston in 1800; the known copies are bound with Sacred Dirges, Hymns, and Anthems, commemorative of the death of General George Washington (Boston, [1800]). The attribution to Holden appears in contemporaneous newspaper sources. A modern edition of the work is available in Oliver Holden (1765-1844): Selected Works, Music of the New American Nation 13, Karl Kroeger, gen. ed. (New York: Garland Publishing, 1998), 183–90.

20. David Moritz Michael, Der 103te Psalm: An Early American-Moravian Sacred Cantata for Alto, Tenor, and Bass Soloists, Mixed Chorus, and Orchestra (1805), ed. Karl Kroeger, Recent Researches in American Music 65 (Middleton, WI: A-R Editions, 2008). Michael’s work is listed in Dox’s bibliography as CA2143.

21. See Thurston Dox’s articles “Samuel Felsted of Jamaica,” The American Music Research Center Journal 1 (January 1991): 37–46, and “Samuel Felsted’s Jonah: The Earliest American Oratorio,” Choral Journal 32, no. 7 (February 1992): 27–32. In 1994, Hinshaw Music published a performing edition of Jonah, edited by Dox.

22. The Boston Handel and Haydn Society had been founded only the year before publication of Hastings’s cantata (1815) and is still an active organization. The New York Handel and Haydn Society was founded in 1817 but gave its last concert in 1821; see Dennis Shrock, Choral Repertoire (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 546, and Vera Brodsky Lawrence, Strong on Music: The New York Music Scene in the Days of George Templeton Strong, vol. 1 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), xxxviii.