“I’LL BRING YOU MORE THAN A SONG”: Right Worship in Evangelical Perspective

Artistic Theologian 10 (2023): 65-83

Benjamin P. Snoek is campus pastor and adjunct professor of theology at Trinity Christian College in Palos Heights, Illinois. He is a Ph.D. candidate in theological studies at Columbia International University and an ordained pastor in the Christian Reformed Church in North America.

Since the debut of contemporary music and instrumentation in public worship services, American Christians have fought vehemently over so-called “worship wars.” Mark Evans notes that “a revolution in Christian music took place in the second half of the twentieth century as the delineation between sacred and secular became increasingly blurred.”2 The use of secular rock and-roll styles, initially designed to appeal to unchurched surfers at Chuck Smith’s Costa Mesa Calvary Chapel, quickly spread across the country. Fueled by music distribution companies such as Maranatha! Music, these new musical influences became perceived as an affront to the organ-driven European worship style that dominated American Protestant worship. Acrimonious, incendiary fights broke out in churches, many of which split congregations. As Lester Ruth writes, “Around 1993, American Protestants declared war on each other. . . . Bitter disagreements, angry arguments, and political machinations spilled across the church. . . . Congregations voted with their feet, or their wallets, or with raised hands if the question of which worship style was right was brought to a vote.”3 Musical style became conflated with good or bad worship; in Monique Ingalls’s words, “musical instruments, ensembles, and media became charged symbols used to represent ‘traditional’ and ‘contemporary’ factions in worship.”4

Arguably, these worship wars persist in many congregations today, albeit at a simmered level. Constance Cherry claims that “while there are still some uprisings here and there, after decades of discord a truce has been called in most places.”5 Although this war over musical styles may have subsided, what if there is another conflict—more covert yet equally urgent facing contemporary worshiping communities? John Witvliet argues that the true worship war goes beyond the traditional/ contemporary divide. “I used to think that the largest worship related division among Protestant churches in the Northern Hemisphere was between worship in so-called traditional and contemporary styles,” Witvliet admits. “But I no longer think that this is the most significant division among congregations. Another, more subtle division emerges over time as far more significant, I believe, for the health and well-being of both individual congregations and Christianity as a whole.”6 Witvliet submits that the most pressing issue facing Christian worship—particularly within evangelicalism—is whether a worshiping community views worship as primarily formative or as primarily expressive.

This article probes and expands Witvliet’s hypothesis and applies it to an understanding of right or (in Melanie Ross’s words) “good” worship.7 It will then attempt to understand the worship wars through this divide, as opposed to a stylistic divide. Indeed, what makes worship “good” goes beyond a matter of style—right, proper worship recognizes its formative and expressive dimensions and brings them out in healthy, wise ways.

DEFINING EXPRESSIVE AND FORMATIVE WORSHIP

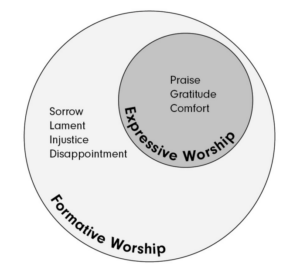

These terms carry a host of connotations in liturgical theology; thus, it is important to parse them as Witvliet understands them.8 By expressive worship, Witvliet is describing “worship which articulates what a congregation is already experiencing. . . . The focus in these contexts is almost entirely on relevance, on matching what happens in the assembly to ‘where the people are at.’”9 By formative worship, Witvliet is describing “worship which does acknowledge where a congregation is at, but is also eager for a congregation to grow beyond where it is into something deeper. . . . The focus is on growth, discipleship, and sanctification—even when these words aren’t explicitly used.”10 Whereas expressive worship emphasizes connecting with people through liturgical practices, formative worship emphasizes shaping people through liturgical practices. Melanie Ross compares formative and expressive worship to two views of a city: expressive worship is a street-level view, focusing more on a worshiper’s immediate needs and surroundings, and formative worship is a bird’s-eye view, focusing more on the holistic sweep of a community’s identity.11 To be sure, it is flawed to perceive formative worship as the opposite of expressive worship. Formation and expression are distinct from one another, with formative worship including all elements of expressive worship and then offering additional elements (fig. 1). Worship, at its best, captures the experiences relevant to a particular community while simultaneously encouraging growth beyond the bounds of what is expressed.

Figure 1. One possible relationship between formative and expressive worship.

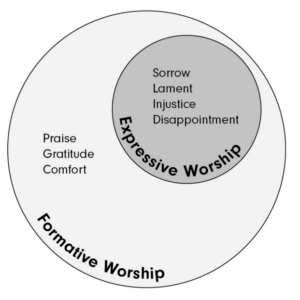

The degree to which the liturgies of a worshiping community are formative or expressive is a matter of content, not of style. Witvliet asserts that “expressive worship arises from congregations deeply attached to the status quo, whether or not the status quo features pipe organs or praise teams.”12 Moreover, the liturgies that make worship formative or expressive are not standardized across cultures. What is formative for some contexts may be expressive for others (fig. 2). For instance, lament in the Black worship tradition could be a natural, expected element of a community’s ethos, while that expression may be unusual for a suburban, Anglo-Saxon congregation. In turn, a white megachurch congregation that relies on music from the Christian Copyright Licensing International Top 100 charts may find that expressive worship emphasizes praise and celebration of God’s blessings over emotions of doubt or sorrow.

Figure 2. One possible relationship between formative and expressive worship that might depict the Black worship tradition, in contrast to fig. 1, which may more likely depict the relationship in a white evangelical congregation.

FORMATIVE AND EXPRESSIVE WORSHIP IN TENSION

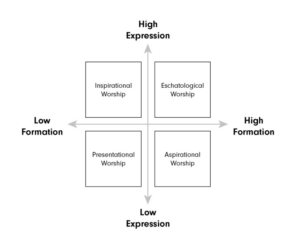

The nuances of formative and expressive worship can be elucidated when placed on a matrix (fig. 3). Witvliet suggests that congregations of any size or style understand worship at varying levels of formation and expression. This section will explore each of these quadrants, from lowest to highest values.

Figure 3. A matrix of formative and expressive worship

LOW FORMATION, LOW EXPRESSION:

PRESENTATIONAL WORSHIP

Worship that is neither expressive nor formative could be called presentational worship, as it seeks to do nothing but present worship without expecting any participation in God’s true intentions for the event.13 The biblical prophets seemed concerned with Israel’s hollow ritualism, presenting worship devoid of substance. God speaks through Amos to rebuke the Israelites’ empty religion. “I hate, I despise your religious festivals,” God laments. “Your assemblies are a stench to me. Even though you bring me burnt offerings and grain offerings, I will not accept them” (Amos 5:21–22, NIV). Likewise, through Malachi, God rejects the unclean offerings of the post-exilic Jews, accusing them of “lighting useless fires on my altar” (Mal 1:10). God’s expectations for worship are clear: “I desire mercy, not sacrifice, and acknowledgment of God rather than burnt offerings” (Hos 6:6). Worshipers are not asked to obsess over the acts of worship but to engage with and become like the one toward whom worship is offered. Matthew Myer Boulton equates presentational worship with idolatry, a= continuation of the Fall, for “the crisis of sin, of separation, of being away and apart from God, takes place as the human attempt to carry out— apart from God—the ‘work of the people.’”14 When God’s standards for worship are ignored in favor of passive rituals that are neither expressive nor formative, presentational worship occurs, and worship fails to achieve its purposes.

LOW FORMATION, HIGH EXPRESSION:

INSPIRATIONAL WORSHIP

Worship that is overly expressive but rarely formative could be called inspirational worship. This approach is a common practice among evangelical/free church worship traditions. Embracing Paul’s motto to “become all things to all people so that by all possible means I might save some” (1 Cor 9:22), worship becomes a pragmatic tool to express limited emotions; chief among them is praise. Scott Aniol claims that “worship for most evangelicals tends to focus on methodology: How many songs will we sing? What instrumentation will we use? In what order will we organize the service?” He concludes that evangelical worship, in general, values immediate needs and preferences. “How we worship is based on cultural conventions, preferences of the people, or tradition,” Aniol writes. “What matters is what we believe and the sincerity of our hearts; how we worship is simply the authentic overflow of our hearts toward God.”15 For Aniol, evangelical worship is prone to pragmatism—selecting liturgical elements and expressions that are most fitting to the context of the particular congregation. When left unbalanced by formative liturgy, this approach to worship can become primarily inspirational. Hyper-expressive worship, then, merely inspires worshipers by confirming their present emotions and experiences.

It could be said that this attitude is prevalent among evangelical Christians, many of whom desire for worship to “fill them up” and create a spiritual “atmosphere.”16 A cursory analysis of many contemporary Christian worship songs would reveal lyrics of enraptured love to or from a vague deity. Worship leaders supplant liturgies of confession with motivational, relevant messages to avoid compounding guilt and to alleviate the cares amassed at the end of a difficult week.17 In some evangelical circles, electronic dance music (EDM) has gained traction in some American congregations, most notably through artists such as Hillsong Young & Free. Although not every congregation relies on an entirely EDM musical style, EDM-influenced worship music is more accessible with the growing popularity of instrumental loop tracks for church worship bands. Explaining the explosion of this new style, Jeff Neely does not cite the worship wars but hints at the allure of expressive worship. “In the case of EDM,” Neely observes, “the genre brings a context for creating a sense of tension and release (e.g., sin and redemption), as well as a sense of community and collective experience. . . . Different musical styles create familiar atmospheres that prime listeners for specific emotional experiences.”18 Neely locates the power of EDM worship in its ability to musically express the theological desires of a congregation. In other words, EDM forms a musical hype that, when left by itself, results in specific and delimited spiritual experiences that are primarily emotional.

he appeal of expressive worship resonates with other cultural contexts that may be suspicious of formative worship, viewing formativeness as stifling to the spontaneous work of the Holy Spirit. Among African Initiated Churches (AICs), many church leaders resist preparation. Peter Nyende

notes that African ecclesiology and worship, situated in a syncretistic milieu that is aware of the spirit world, are sourced in “the intersection of Africa’s spiritual enchanted world and the Christian faith.”19 Cas Wepener and Mzwandile Nyawuza observe that, among South African indigenous leadership in worship, “the most important aspect . . . is what we will call ‘life in the Spirit,’ meaning a certain kind of spirituality that connects closely to an African worldview regarding the world of the Spirit and the spirits.”20 By “life in the Spirit,” Wepener and Nyawuza refer to spiritual gifts such as prophecy, gift recognition, and healing as marks of liturgical leadership—a Christian reaction against a pagan worldview.21 Worship in AICs, generally speaking, favors expression over formation, for it is in the immediateness of expressive liturgy that the Holy Spirit can demonstrate God’s power among false spirits.

There is a necessary place in worship for expressing immediate desires and experiences. The problem with hyper-expressive (inspirational) worship, however, is that it does not represent the multitude of experiences that people bring to worship. Not all who gather for worship are ready to offer words of praise before God. Consider a family who comes to church mere days after grieving a miscarriage, or a blue-collar worker laid off due to a pandemic from a job she held for decades, or a white college student confused about how to steward his privilege in light of racial inequality. A liturgical telos of inspiration is insufficient when there are other emotions that urgently long to be expressed. Indeed, “bearing one another’s burdens” (Gal 6:2) and “offering your bodies as a living sacrifice” (Rom 12:1) require that those gathered for worship corporately express the fullness of their collective imagination—even if an individual has not experienced it yet—before God and each other. In short, inspirational worship fails to adequately communicate a worshiping community’s entire prayer to God.

Furthermore, if expressive worship does not include formative elements, it forfeits the ability to truly shape the ethos of a worshiping community. When faced with the choice between expressive or formative worship, Ross argues that “the temptation for many congregations is to focus on the former at the expense at the latter,” which results in “an enormous amount of literature on how to improve or maximize the experience of worship, but relatively few resources that address what kind of people we are forming with our worship over the course of their lifetimes.”22 Worship is meant to express more emotions and experiences beyond those which are individualized or preferred, given that worship forms a congregation’s identity. Rhys Bezzant asserts that “the responsibility for corporate identity formation falls ever more heavily on the local congregation. God’s people respond to God’s voice, not just individually, but primarily as a body.”23 When a congregation “learns to clothe itself with corporate categories and experiences,” worship shapes the entirety of Christian community’s spiritual ethos.24 Thus, inspirational worship falls short in its ability to represent a decidedly corporate identity through its liturgy.

HIGH FORMATION, LOW EXPRESSION:

ASPIRATIONAL WORSHIP

In contrast, worship that is excessively formative but barely expressive becomes aspirational worship. This approach is a common understanding of worship among so-called “liturgical” traditions.25 Of course, it is unrealistic to express the entirety of a congregation’s experiences in a seventy-minute service. Nonetheless, traditions that rely on slower, repetitive rituals with less immediate results capture the beauty of formative worship. When liturgy is formative, it offers a rich, balanced diet of prayer to God, facilitated by tools such as the lectionary and the Christian year. Rather than selecting Scripture readings according to topical needs, the lectionary gradually covers most of the biblical terrain with corresponding collect prayers each week. Similarly, the Christian calendar allows worshipers to participate in God’s redemptive story through the calendar year—the contours of anticipation during Advent, wonder during Epiphany, penitence during Lent, joy during Easter, and mission during Pentecost. Robert Webber advocated for “Christian-year spirituality,” where “piety is based on this pilgrimage throughout the year.”26 Webber refers to such practices that shape worshipers over time as “a formative approach to God’s saving events.”27 Whereas expressive worship may highlight a congregation’s immediate “holy days” (such as Mother’s Day, Independence Day, or Baptism Sunday for local parishes, or Commencement, Revival Week, or Alumni Day for college and university chapel congregations), formative worship insists on wider liturgies that accompany longer-range formation.

Although formative worship has immense strengths, it can become burdensome when left unbalanced. Aspirational worship creates unmanageable goals, as these formative elements are not sourced within the needs of a particular context. It may seem ironic that worship can be hyper-formative. However, just as the prophets criticized the ritualism of presentational worship, aspirational worship can easily slip into liturgy for liturgy’s sake, devoid of meaning for the worshiper. The season of Advent may call forth a longing for Christ’s return, but this desire for peace is more spiritually significant when expressed through the prayers in a global pandemic, lamenting loneliness, divisiveness, and the loss of hundreds of thousands of lives. Put another way, formation may be the ending point of liturgy, but expression offers the starting point. Expressive liturgy strengthens formative liturgy by locating formation within the needs of a particular worshiping community. Like a spiritual guide, formative worship gives new words of prayer into which worshipers can grow, while its expressive dimension anchors their prayers in their current spiritual status.

Accordingly, worship that does not attempt to connect with a congregation by means of expressive liturgy creates barriers to participation. Curiously, even excessively formative worship can inhibit long-term spiritual formation. Ruth traces the formalization of worship to the medieval period, when “prayers and other liturgical texts became written down, edited, combined, scrutinized, shared, and standardized as families of liturgical rites associated with large regions developed,” leading to services that were almost “entirely scripted.”28 “The danger . . . of such acts of worship,” Ruth worries, “is that it becomes easy to see them as things or objects to be checked off in the order of worship. It is easy to forget what they essentially are: a way of doing some vital worshipping activity toward God.”29 Left unbalanced, treasured liturgies such as the Te Deum, the Kyrie Eleison, or the Doxology can easily become “a sequence of liturgical objects, not a flow of worshipful actions.”30 As Bezzant writes, “One of the chief concerns expressed by evangelicals regarding formal liturgies is their power to alienate. . . . Repetition or recitation is thought to conform to an infantile pedagogy. A set‐piece order does not take into account local needs or opportunities.”31 Proper worship resists the perils of aspirational worship—liturgical ritual with no clear relevance for the worshiping community.

In short, for formative liturgy to be truly formative, it must also contain expressive elements. Here is where an “empathetic imagination,” to borrow Fred Craddock’s words, becomes imperative. Craddock defines this type of empathy as “the capacity to achieve a large measure of understanding of another person without having had that person’s experiences.”32 By gaining a sufficient understanding of worshipers’ desires, struggles, values, and circumstances, a worship pastor can use empathy in order to build bridges from the world of the liturgy to the world of the worshiper. Those who lead worship in ways that attend only to the liturgy but not to the people performing the liturgical acts neglect pastoral awareness. Indeed, a myopic approach, for Witvliet, creates liturgists who “will lack the motivation to diagnose and treat the liturgical diseases that keep congregations from genuine spiritual health.”33 Formative worship becomes aspirational worship when it remains irrelevant and artificial, failing to recognize the unique context in which it is expressed.34 Wise are the worship leaders who take seriously their pastoral duties, fashioning words of prayer that are both accessible and challenging.

HIGH FORMATION, HIGH EXPRESSION:

ESCHATOLOGICAL WORSHIP

At its best, worship is both highly expressive and highly formative. Thankfully, there is neither a choice nor a compromise needed between them. “Good worship is both formative and expressive,” Ross declares. “It is attentive to both the short-term impact of a seventy-five-minute service, and the long-term spiritual formation that happens over the course of several decades.”35 The rituals of the church are inherently multivalent. Bernard Cooke and Gary Macy refer to rituals as, in part, containing a “hermeneutic of experience” and a tool for maturation—a similar parallel to Witvliet’s binary division of expressive and formative worship. As a “hermeneutic of experience,” rituals give “a particular way of understanding the world” and “celebrate and reinforce this understanding.”36 As a tool for spiritual development, rituals “help Christians ‘grow up’ . . . and each ritual offers the possibility of a further maturation.”37 Worship must address immediate needs while simultaneously recognizing that one of these needs is to shape worshipers for a life of discipleship.38 The rituals that constitute Christian worship “mark the many stages of maturation within groups and societies,”39 offering means through which worshipers can “work out their salvation” (Phil 2:12) and “grow in grace” (2 Pet 3:18).

Worship can be both expressive and formative regardless of style or context. For instance, Orbelina Eguizabal challenges notions of Latino worship that portray it as a mere expression of Latino culture or a sacred fiesta. Instead, Eguizabal asserts, Latino worship is a highly formative event expressed within a Latino context. She explains that “spiritual formation evolves around the activities that are held on Sunday morning or afternoon, because the Sunday gathering is the main activity for members. Church leaders try to make it work for everybody’s needs.”40 In addition to a worship service and Sunday school class, Eguizabal observes that Latino worship typically includes times of fellowship throughout the gathering, which may include refreshments, greeting with hugs, short prayers that interrupt conversations, or even complete meals.41 An extended fellowship time is a formative ritual rooted in an expressive desire (“making it work for everybody’s needs” on an important day for Latino Christians). This time “helps adults and children get to know each other, encourage each other in their walk with the Lord, and build community.”42 Intentionally structured according to its cultural style, this form of worship among Latino communities pays attention to immediate needs while facilitating opportunities for long-term, corporate growth.

Witvliet’s vision of formative and expressive worship is sourced in a robust understanding of covenantal worship. Witvliet refers to worship as “God’s language school,” a metaphor borrowed from Thomas Long.43 The liturgies of Christian worship are pedagogical devices, training worshipers to speak to God in ways that are both familiar (expressive prayer) and distant (formative prayer). As Witvliet writes, “When we gather for worship, the church invites us to join together and say to God . . . a series of communal speech acts. . . . The problem is that, like toddlers, we don’t have a natural inclination to say any of these things to God. . . . If we are not formed to do so, none of us are all that likely to say to God half the things we say in the liturgy.”44 Witvliet presupposes public worship as a covenant renewal ceremony, an event that allows the exchange of “communal speech acts.” Scripture describes such ceremonies, during which God’s promises with God’s people are sealed through ritual (cf. Exod 34; Josh 24). God makes promises, and God’s people make promises back.45 Liturgy allows this conversation to be “genuinely formative of nothing less than a corporate covenantal relationship with God.”46 This interaction—an active dialogue, not a monologue—is made possible through the work of Jesus, the “mediator of a new covenant” (Heb 9:15).

When liturgy is both formative and expressive, it enables worshipers to hear from God and speak to God in ways that are both familiar and fresh, comforting and challenging. It recognizes that God’s covenantal relationship encompasses more expressions of faith than those of a single worshiper. Hence Witvliet writes:

The liturgy, fortunately, gives room for all these essential words.

It helps each of us express our particular experience, but it also invites

us to practice the language that represents what someone else is

experiencing. Authentic worship involves both expressing our deepest

feelings in the moment and practicing the best relational habits in our

common covenant with God in Christ.47

Bezzant likens proper worship to a formative, holistic drill in which “a well-conceived liturgy provides for individual Christians an opportunity to exercise several spiritual muscles, using various apparatuses.”48 Bezzant is careful to note that the exchange of words does not limit itself to cognitive understanding. In liturgical contexts, he claims, “minds, hearts, wills and imaginations can all be engaged through the power of words. Cumulatively, words are performative apparatuses (not merely information manuals) when embedded within a ritual structure.”49 This “power of words,” located within the dynamism of formative and expressive worship, allows worship to transform lives.

This form of worship could be labeled eschatological worship, as it recognizes the healthy tension between the “already” (expression) and the “not yet” (formation). True enough, all worship is eschatological; through the liturgy, worshipers participate in the kingdom of heaven on earth.50 Thus, the worshiping community is an eschatological community, participating in rituals that point toward and usher in God’s kingdom. Jean-Jacques von Allmen spoke of worship as an “eschatological game,”51 and Geoffrey Wainwright envisions the church at worship as a representation of the already-not-yet eschatological tension. “The worship of God is the most eschatological activity of the church, since it will endure into the final kingdom and indeed become so all-pervasive that there will be no need for a temple in the city of God,” he states.52 When worship is both highly expressive and highly formative, worship is highly eschatological.

In the liturgies of an eschatological worshiping community, the formative dimensions prepare worshipers for citizenship in heaven (cf. Phil 2:20), while the expressive dimensions ground worship on earth. Earthly worship intersects with eternal worship in its rituals. Stanley Hauerwas asserts that “those rites, baptism and Eucharist, are not just ‘religious things’ that Christian people do. . . . It is in baptism and eucharist that we see most clearly the marks of God’s kingdom in the world.”53 For Hauerwas, worship, particularly the sacraments, marks the presence of a countercultural reality on earth and points toward God’s kingdom. These ordinary signs and symbols, expressed within a particular worshiping community, become portals into a future hope. Thus, God expects songs of celebration and prayers of thanksgiving. At the same time, God expects worshipers to pray for their enemies and preach sermons that mourn and decry sins of injustice, for these “communal speech acts” point toward the world that God is shaping. These formative acts are not politically motivated but kingdom-motivated—indeed, such are the liturgies that Jesus sees as necessary in his kingdom (Matt 5).

Another clear example of eschatological worship can be observed in singing songs from other cultures. Swee Hong Lim insists that singing global songs in North American contexts is not a matter of increasing diversity, satisfying preferences, or cultivating authenticity. Instead, through music-making, the Holy Spirit “enfolds the singing community into a fellowship that includes the Other.”54 Thus, “the songs are no longer songs of the Other but are our songs as well—particularly when we subscribe to the understanding of being united in the one Spirit.”55 For Lim, good worship incorporates songs from foreign lands into a familiar community for the sake of “sonic hospitality.” “The ‘right’ worship is worship that actively divests power from the empire to the subaltern—even in the choice of worship leadership,” Lim declares. “It is worship that endeavors to honor diversity at God’s table, recognizing that all are in one fellowship of the Spirit. This worship approach recognizes that diversity provides a clearer perspective into the realm of God, which has justice and peace as its hallmark.”56 Worship leaders do not incorporate global songs into the liturgy of an English-speaking, North American congregation to be politically sensitive or culturally relevant; there is a much larger agenda dominating such decisions. When worshiping communities welcome and sing the “songs of the Other,” these once-formative words become expressive while signaling a future reality, where the liturgy includes songs that voice the faith of “every nation, tribe, people, and language” (Rev 7:9).

Put simply, proper worship inculcates an eschatological worldview. When worship contains a wise mix of liturgies that are both highly expressive and highly formative, these rituals shape worshipers into people who see the world as God sees it and who treat the world as God treats it. Alexander Schmemann describes corporate worship as “a vantage point from which we can see more deeply into the reality of the world.”57 Similarly, Wolfhart Pannenberg looks to the church’s gathering as a signal of the eschaton. “What the church does most distinctively serves the world most powerfully,” Pannenberg writes. “It is precisely as a liturgical worshiping community that the church is most effectively a sign of the ultimate destiny of every human being and of humanity as a whole.”58 The qualities of proper worship, then, move beyond relevance or preference; instead, right worship shapes worshipers into the people of God.

RE-INTERPRETING THE WORSHIP WARS IN LIGHT

OF THE FORMATIVE/EXPRESSIVE DIVIDE

Witvliet explains that the issue of music was at the “front line of combat” in the worship wars.59 “The worship wars of the past decade are about nothing more than music—what music will be sung, what style it will be, who will lead it, what instruments will be used, and how loud it will be,” he claims.60 Witvliet now maintains that the primary divide between congregations is not over superficial matters of musical style. Instead, the real dispute behind the worship wars is whether a congregation chooses to view worship as primarily formative or primarily expressive. Perhaps it is possible to re-interpret the worship wars in light of Witvliet’s proposed divide. If debates over worship have largely surrounded “nothing more than music,” then how could issues of formation and expression enhance these conversations?

Undergirding the ardent cases for a particular style, whether traditional hymns, contemporary music, or a blend of both, is a theological preference—a decision on how to view the essence of worship. Common arguments for one style over another tend to target the function of the style. An expected case for hymns, for instance, might say that hymns are superior because they teach theology, while contemporary Christian music (CCM) does not. This argument describes a theological preference within a style, claiming that hymns are formative (in that they teach a wide variety of experiences with God), and CCM is not. Conversely, an expected case for CCM might say that CCM emphasizes a new, fresh expression of a relationship with God. Hymns, in turn, are stale and lifeless. This theological preference favors the expressiveness found in CCM lyrics and music, perceived as more relevant and therefore better.

There are significant limitations to viewing the worship wars merely as a style debate. The fault lines become apparent when one extrapolates these arguments. Doctrinal truth may be formed in hymns such as Fanny Crosby’s “To God Be the Glory,” but how could the same standards apply to subjective hymns like Charles Wesley’s “Jesus, Lover of My Soul”? Likewise, Cory Asbury’s “Reckless Love” and Sinach’s “Way Maker” may long for a new inbreaking of the Spirit, but what about contemporary songs such as Hillsong’s “King of Kings” or “This I Believe (The Creed),” which teach a strong Christology? It is no surprise that Witvliet calls these style-driven debates “problematic discussions” that “tolerate abstract and nebulous arguments.”61 The worship wars have become a pragmatic lens through which a worshiping community chooses to understand the essence—formative or expressive—of worship.

Placing the worship wars along a formative/expressive divide rather than a traditional/contemporary divide reveals an urgent issue. A functional or pragmatic approach to worship style lacks the opportunity for deeper conversations on why worship matters. As Byron Anderson writes, “Missing in both this pragmatic turn and in the conflict between ‘traditional’ and ‘contemporary’ worship is significant discussion of what is at stake for the identity of Christian persons and communities in the shape and practice of worship.”62 Conversations that operate on lower-level issues of style threaten genuine worship renewal efforts, as they will never ascend to the more pressing conversations on whether worship will be formative or expressive. Witvliet is correct: “Questions about ‘right liturgy’ deserve more than an answer. They beg for a discussion of underlying rationale.”63 Although there may be lively, endless discussions on what makes worship preferable or relevant, there will be far fewer on what makes worship, at its very essence, “good.”

CONCLUSION: THE ANGULARITY OF

LITURGICAL THEOLOGY

“Right” worship is both formative and expressive, resisting the respective extremes of aspirational and inspirational worship. Witvliet insists that worship not only allows worshipers to express what is on their hearts now but prepares them for the many emotions and words that they will find themselves hearing from and speaking to God. Cherry summarizes the matter well: “Songs influence us. They both express who we are and call us to who we can become.”64 Such could be said of any liturgy: sung or spoken, public or private, formal or informal. Regardless of cultural context or musical style, from organs to guitars to congas, worship leaders, pastors, and church musicians will always face the decision to include primarily expressive or primarily formative liturgies—whether they realize it or not.

Christian worship is shared faith expressed and formed through ritual. This article explored Witvliet’s understanding of worship as formative and expressive and argued that this framework is a clearer lens through which one can view the divide between today’s and tomorrow’s worshiping communities. Further research is necessary on this issue, especially to connect the theological dimensions of formative and expressive worship with the historical development of contemporary evangelical worship. This article has called for conversations among scholars of liturgy and church music on the essence of worship that dig deeper than stylistic preferences. A matrix of formation and expression reframes the worship wars by its substance rather than its style, allowing researchers and practitioners in liturgy to have more profound conversations about proper worship.

2. Mark Evans, Open Up the Doors: Music in the Modern Church (Oakville, CT: Equinox Publishing, 2006), 38.

3. Lester Ruth, “The Eruption of the Worship Wars: The Coming of Conflict,” Liturgy 32, no. 1 (2017): 3.

4. Monique M. Ingalls, Singing the Congregation: How Contemporary Worship Music Forms Evangelical Community (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 6.

5. Constance M. Cherry, The Music Architect: Blueprints for Engaging Worshipers in Song (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2016), 176.

6. John D. Witvliet, Series Preface to What Language Shall I Borrow?: The Bible and Christian Worship, by Ronald P. Byars (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2008), xi.

7. Melanie Ross, “Good Worship: An Evangelical Free Church Perspective,” Liturgy 29, no. 2 (2014), 3.

8. Witvliet is not the only liturgical scholar who speaks of worship in terms of formation and expression, to be sure. It is noteworthy, nonetheless, that Witvliet locates the true source of liturgical conflict within formative and expressive substances rather than contemporary and traditional styles.

9. Witvliet, Series Preface to What Language Shall I Borrow?, xi–xii.

10. Witvliet, Series Preface to What Language Shall I Borrow?, xi–xii.

11. Ross, “Good Worship,” 3.

12. Witvliet, Series Preface to What Language Shall I Borrow?, xi. This claim could also be applied to formative worship.

13. It is worth considering whether such worship even exists in a way that could be considered decidedly Christian. Since this article focuses on worship when it is formative and/or expressive, less attention will be given to this quadrant of the matrix.

14. Matthew Myer Boulton, God against Religion: Rethinking Christian Theology through Worship (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2008), 50.

15. Scott Aniol, “As We Worship, So We Believe,” Artistic Theologian 8, no. 1 (2020): 2.

16. From observation, these vague terms are ubiquitous in the evangelical worship vernacular.

17. Witvliet raises an interesting question on this topic: “Why do so many churches resist confessing sin or lamenting brokenness ‘because sincerity on these matters can’t be forced,’ while singing songs demanding extravagant praise without a similar concern?” (John D. Witvliet, “The Mysteries of Liturgical Sincerity,” Worship 92 [May 2018]: 200).

18. Jeff Neely, “Worship with a Drop: Why Churches Are Turning to Club Music to Elevate Praise,” Christianity Today 61, no. 6 (August 2017): 53.

19. Peter Nyende, “The Church as an Assembly on Mt. Zion: An Ecclesiology from Hebrews for African Christianity,” in The Church from Every Tribe and Tongue: Ecclesiology in the Majority World, ed. Gene L. Green, Stephen T. Pardue, and K. K. Yeo (Carlisle, UK: Langham Global Library, 2018), 151.

20. Cas Wepener and Mzwandile Nyawuza, “‘Sermon Preparation Is Dangerous’: Liturgical Formation in African Initiated Churches,” Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 157 (March 2017): 181.

21. Wepener and Nyawuza, “Liturgical Formation,” 181.

22. Ross, “Good Worship,” 3.

23. Rhys Bezzant, “The Future of Liturgy: An Evangelical Perspective” (Spiritual Studies Institute, Ridley College, Melbourne, 2012), 5.

24. Bezzant, “The Future of Liturgy,” 5.

25. The liturgical tradition is an established term referring to a worship style with relatively fixed liturgies, often featuring prescribed prayer books or missals. This term is not a comment on its ritualistic qualities; to be sure, all worship is, in a sense, liturgical.

26. Robert E. Webber, Ancient-Future Time: Forming Spirituality through the Christian Year (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2004), 32.

27. Webber, Ancient-Future Time, 32.

28. Lester Ruth, “An Ancient Way to Do Contemporary Worship,” in Flow: The Ancient Way to Do Contemporary Worship, ed. Lester Ruth (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2020), 8.

29. Ruth, “An Ancient Way to Do Contemporary Worship,” 9.

30. Ruth, “An Ancient Way to Do Contemporary Worship.” A similar claim could be made for the free church tradition: Left unbalanced, the three-song setlist, prayer, and sermon can easily become “a sequence of liturgical objects, not a flow of worshipful actions.”

31. Bezzant, “Future of Liturgy,” 4.

32. Fred B. Craddock, Preaching (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2010), 39.

33. John D. Witvliet, “Teaching Worship as a Christian Practice,” in For Life Abundant: Practical Theology, Theology Education, and Christian Ministry, ed. Dorothy C. Bass and Craig Dykstra (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2008), 145.

34. For instance, penitence may be a formative element for a congregation, but perhaps a confession liturgy may need to be adapted with progressively targeted language. Likewise, perhaps the opening prayer should include a reference to a recent local tragedy

35. Ross, “Good Worship,” 4.

36. Bernard J. Cooke and Gary Macy, Christian Symbol and Ritual: An Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 52.

37. Cooke and Macy, Christian Symbol and Ritual, 52.

38. This approach reframes conversations about liturgies such as the prayers of the people and even the announcements—both of which express the needs of a congregation with a view to long-term formation.

39. Cooke and Macy, Christian Symbol and Ritual, 28.

40. Orbelina Eguizabal, “Spiritual Formation of Believers among Latino Protestant Churches in the United States,” Christian Education Journal 15, no. 3 (2018): 429.

41. Eguizabal, “Spiritual Formation of Believers among Latino Protestant Churches,” 429.

42. Eguizabal, “Spiritual Formation of Believers among Latino Protestant Churches,” 430.

43. “Worship is a key element in the church’s ‘language school’ for life. . . . It’s a provocative idea— worship as a soundtrack for the rest of life, the words and music and actions of worship inside the sanctuary playing the background as we live our lives outside, in the world” (Thomas G. Long, Testimony: Talking Ourselves into Being Christian [San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2004], 47–48).

44. John D. Witvliet, “Liturgy as God’s Language School,” Pastoral Music 31, no. 4 (2007): 19.

45. Witvliet—true to his Reformed identity—relies heavily on the Psalms as the “script” and “mentor” for this covenantal interaction. For Witvliet, the Psalms capture the fullness of the human experience toward God, self, and world. See John D. Witvliet, The Biblical Psalms in Christian Worship: A Brief Introduction and Guide to Resources (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007).

46. Witvliet, “Liturgy as God’s Language School,” 23

47. Witvliet, “Liturgy as God’s Language School,” 19–20.

48. Bezzant, “Future of Liturgy,” 9.

49. Bezzant, “Future of Liturgy,” 9. Lutheran theologians also see worship as a “foretaste of eternity”; see Eric Chafe, Tears into Wine: J. S. Bach’s Cantata 21 in Its Musical and Theological Contexts (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015).

50. The eschatological dimensions of evangelical ecclesiology are indebted to Catholic and Orthodox theologies, which emphasize the intersection of heaven and earth. The Sacrosanctum Concilium, a constitution on liturgical renewal from the Second Vatican Council, states: “In the earthly liturgy we take part in a foretaste of that heavenly liturgy which is celebrated in the holy city of Jerusalem toward which we journey as pilgrims, where Christ is sitting at the right hand of God, a minister of the holies and of the true tabernacle” (“In terrena Liturgia caelestem illam praegustando participamus, quae in sancta civitate Ierusalem, ad quam peregrini tendimus, celebratur, ubi Christus est in dextera Dei sedens, sanctorum minister et tabernaculi ver”) (Second Vatican Council, Sacrosanctum Concilium, quoted in David Lysik, ed., The Liturgy Documents: A Parish Resource, 4th ed. [Chicago: Liturgy Training Publications, 2004], 1:5).

51. Jean-Jacques von Allmen, “Worship and the Holy Spirit,” Studia Liturgica 2 (1963): 124–35.

52. Geoffrey Wainwright, Worship with One Accord: Where Liturgy and Ecumenism Embrace (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 31.

53. Stanley Hauerwas, The Peaceable Kingdom: A Primer in Christian Ethics (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1983), 108.

54. Swee Hong Lim, “What Is the Right Kind of Worship . . . If You Want North American Congregations to Sing Global Songs?,” Global Forum on Arts and Christian Faith 5, no. 1 (2017): 51

55. Lim, “What Is the Right Kind of Worship?,” 51.

56. Lim, “What Is the Right Kind of Worship?,” 53.

57. Alexander Schmemann, For the Life of the World: Sacraments and Orthodoxy, 2nd ed. (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2004), 27.

58. Wolfhart Pannenberg, “The Present and Future Church,” First Things, November 1991, 49.

59. John D. Witvliet, “Beyond Style: Rethinking the Role of Music in Worship,” in Worship at the Next Level: Insight from Contemporary Voices, ed. Tim Dearborn and Scott Coil (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2015), 164.

60. Witvliet, “Beyond Style,” 164.

61. Witvliet, “Beyond Style,” 165.

62. E. Byron Anderson, Worship and Christian Identity: Practicing Ourselves (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2003), 2.

63. Witvliet, “Teaching Worship,” 144.

64. Cherry, Music Architect, 236.