“I Wanna Talk about Me”: Analyzing the Balance of Focus between God and Man in Congregational Songs of the American Evangelical Church

Artistic Theologian 9 (2021): 19–41

Nathan Burggraff, PhD, is assistant professor of music theory and director of the music theory and piano departments at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary.

Narratives in contemporary culture have become increasingly narcissistic. This is cleverly illustrated in Toby Keith’s 2001 hit country song “I Wanna Talk about Me.” The song’s two verses lament the fact that the singer’s girlfriend only ever talks about herself. This in itself shows the girlfriend’s own narcissism. The song’s chorus then presents an ode to the singer, who would like to talk about himself once in a while:

I wanna talk about me

Wanna talk about I

Wanna talk about number one

Oh my me my

What I think, what I like, what I know,

what I want, what I see

I like talking about you, you, you,

you usually, but occasionally

I wanna talk about me

I wanna talk about me.

While the song is meant to poke fun of narcissistic and self-absorbed girlfriends, it also shows a reality for most people: we like talking about ourselves. Unfortunately, contemporary culture continues to provide more and more outlets for people to talk about and promote themselves: Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, self-started blogs, etc.

In his book The Divine Embrace: Recovering the Passionate Spiritual Life, Robert Webber contends that the church has embraced this culturally driven narrative, resulting in me-oriented worship that sees God as the object of man’s worship rather than the subject:

Me-oriented worship is the result of a culturally driven worship. When worship is situated in the culture and not in the story of God, worship becomes focused on the self. It becomes narcissistic. . . . The real underlying crisis in worship goes back to the fundamental issue of the relationship between God and the world. If God is the object of worship, then worship must proceed from me, the subject, to God, who is the object. God is the being out there who needs to be loved, worshiped, and adored by men. Therefore, the true worship of God is located in me, the subject. . . . If God is understood, however, as the personal God who acts as subject in the world and in worship rather than the remote God who sits in the heavens, then worship is understood not as the acts of adoration God demands of me but as the disclosure of Jesus, who has done for me what I cannot do for myself. In this way worship is the doing of God’s story within me so that I live in the pattern of Jesus’s death and resurrection.[2]

As Webber states, all of creation and history reveals God as the subject. This is what should be celebrated in worship. Webber continues, “Biblical worship tells and enacts [God’s] story. Narcissistic worship, instead, names God as an object to whom we offer honor, praise, and homage. Narcissistic worship is situated in the worshiper, not in the action of God that the worshiper remembers through Word and table.”[3]

Scope of the Analytical Study

Several recent studies have analyzed contemporary congregational song lyrics, in relation to point of view or Trinitarian content, in order to address this perceived shift of focus.[4] Specifically, Daniel Thornton’s 2016 dissertation examines the balance of focus between references to God and references to man in 25 popular contemporary congregational songs, arguing that the lyric content in contemporary songs is predominantly God-centered, despite claims to the contrary.[5]

Expanding upon Thornton’s initial research, the following corpus study analysis identifies and clarifies changes in the balance of focus between God and man in congregational songs over time. The corpus consists of song lyrics in 506 songs currently sung in American evangelical churches, as well as the 150 Old Testament Psalms. The content of the song corpus is based on ranked lists from Christian Copyright Licensing International (CCLI), PraiseCharts, and Hal Leonard.[6] The analysis includes a tabulation of the number of references to man through personal pronouns implying man, as well as the number of references to God, both through pronouns implying God and direct names for God. The tabulation of God and man references was compared in each song in order to determine balance of focus.

One question that arises in this kind of tabulation analysis is determining what to do with repeated lyrics in a song. In previous lyric analysis studies conducted in Ruth 2015 and Thornton 2015, song lyrics were counted only once, even if notated to be sung multiple times. My tabulation analysis, however, is based on the form of the song, taken from the lead sheets on CCLI, to determine how many times particular passages of lyrics are sung in a song. While not every congregation will sing a song in exactly the same form, the CCLI lead sheets provide an objective standard from which to compile the statistical data, as well as to consider actual musical practice.

The songs in the main corpus (406 songs) were compiled into five time periods to reflect music changes over time: (1) songs written prior to 1970, (2) songs written from 1970 to 1989, (3) songs written from 1990 to 1999, (4) songs written from 2000 to 2009, and (5) songs written from 2010 to 2019. Additional mini corpus studies were conducted on the top 50 songs by the Gettys and by Sovereign Grace, based on popularity in CCLI data, and compared to the main corpus song data. The 150 Old Testament Psalms were also compared with the main corpus song data in order to assess potential differences or similarities between them.

A potential issue with tabulating references to God and man in the Old Testament Psalms is the text language used for analysis. One could argue that any English translation of the original Hebrew language will provide grossly inaccurate tabulation numbers. This is true to an extent; however, while the number of pronoun references in English translations greatly exceed those in the original Hebrew, the ratio of first-person to second-person to third-person references is very close between the original Hebrew language and the English translations, as seen in table 1.[7] Having compared the ratios between the English Standard Version (ESV), New American Standard Bible (NASB), and the King James Version (KJV), the ESV is the closest of the three to the percentages of the original Hebrew language. Therefore, the ESV was the chosen version to use for tabulation of pronouns and direct names for God.

Table 1. Instances and Percentages of Pronouns in the 150 Old Testament Psalms

| Hebrew | ESV | NASB | KJV | |||||

| 1st Person Singular | 1675 | 42.0% | 2395 | 42.6% | 2427 | 42.6% | 2439 | 42.7% |

| 2nd Person | 1337 | 33.5% | 1806 | 32.1% | 1810 | 31.8% | 1819 | 31.9% |

| 3rd Person | 979 | 24.5% | 1418 | 25.2% | 1461 | 25.6% | 1453 | 25.4% |

| Total: | 3991 | 5619 | 5698 | 5711 | ||||

Analyzing References to God

The first focus of the analysis was to look at references to God, both through pronoun usage and direct naming of God. Direct names include names that would indicate God as Father, Son, or Holy Spirit. However, words such as “fortress,” “rock,” etc., were excluded from a tabulation of direct names of God, since these refer to images for God rather than names for God. There are several interesting results of this analysis, as shown in table 2. First, the number of songs using the second-person pronoun for God (you/your), within the main corpus of songs, doubles from songs prior to 1970 to songs written after 1990. The Old Testament Psalms sit somewhere in the middle to upper range of those averages. The Gettys follow similar statistics as traditional hymnody, while Sovereign Grace follows contemporary lyric practices. Second, songs that use the third person pronoun (he/him), indicating a more formal, distant aspect, decrease by almost half from songs prior to 1970 to songs written after 1990. The traditional hymnody songs follow closely with the Old Testament Psalms, as do songs by the Gettys. Third, the number of songs directly naming God decreases steadily in songs after 1970, to the point that after 1990, more than 16% of songs within the main corpus do not directly name God even once! This means that these songs only use pronouns to refer to God, or use imagery to depict God, without formally addressing God. Conversely, every Psalm in the Old Testament formally names God at least one time.

Table 2. Percentage of Songs that Reference the Godhead in Each Category

| Psalms | <1970 | 1970–1989 | 1990–1999 | 2000–2009 | 2010–2018 | Gettys | Sov. Grace | |

| You / Your | 69.3 | 42.1 | 51.7 | 88.0 | 82.4 | 83.0 | 46.0 | 92.0 |

| He / Him | 76.0 | 70.7 | 53.3 | 24.0 | 45.6 | 37.5 | 76.0 | 54.0 |

| Direct Names | 100.0 | 98.6 | 95.0 | 84.0 | 83.8 | 84.1 | 98.0 | 96.0 |

| % of: | 150 Psalms | 140 songs | 60 songs | 50 songs | 68 songs | 88 songs | 50 songs | 50 songs |

In regard to the lack of direct reference to the Godhead in contemporary congregational songs, Mark Evans mentions two possibilities for this.[8] One possibility is that secularization in culture is creeping into the church. However, Evans argues against this, since often these songs are simply personal responses to the praise of God, without naming Him. The second possibility is the idea that these songs are, as in the Jewish tradition, the “not-yet-holy” songs. Anything can be holy if Christians ascribe to the song aspects of God’s grace and design. This promotes the idea of being in the world but not of it, which is riskier and a balancing act with songs in the church. Evans states, however, “this is exactly the process major congregational song producers and the huge Contemporary Christian Music (CCM) industry are involved in. They take the music of the secular culture and ‘redeem’ it, by bringing it into the Church and giving it holy meanings and functions.”[9] Conversely, John Fischer argues just the opposite in his 1994 book On a Hill Too Far Away: Putting the Cross Back into the Center of Our Lives:

God has always preferred to put his messages at odds with the world. More often than not, he slants his messages counter-culturally. He works against the grain. . . . Jesus stood both inside and outside of culture. This ability of the gospel to transform as well as transcend—to stand outside of culture as well as inside—is the aspect of the gospel that our present contemporary efforts lack.[10]

Table 3. Percentage of Songs that Directly Name the Godhead and the Number of Times the Godhead is Directly Named in the Song

| Psalms | <1970 | 1970–1989 | 1990–1999 | 2000–2009 | 2010–2018 | Gettys | Sov. Grace | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 5.0 | 16.0 | 16.2 | 15.9 | 4.0 | 6.0 |

| 1 or more | 100.0 | 98.6 | 95.0 | 84.0 | 83.8 | 84.1 | 96.0 | 94.0 |

| 2 or more | 99.3 | 91.4 | 81.7 | 82.0 | 80.9 | 78.4 | 94.0 | 84.0 |

| 5 or more | 76.7 | 57.9 | 48.3 | 56.0 | 63.2 | 55.7 | 72.0 | 64.0 |

| 10 or more | 32.0 | 25.7 | 18.3 | 22.0 | 41.2 | 39.8 | 30.0 | 30.0 |

| % of: | 150 Psalms | 140 songs | 60 songs | 50 songs | 68 songs | 88 songs | 50 songs | 50 songs |

As table 3 shows, while the percentage of songs with no direct naming of God is roughly 16% in songs written after 1990, the number of times God is referenced in songs is not as off-balanced. For instance, the percentage of songs referencing God at least five times is around 58% in songs written before 1970, which is roughly the same, or even lower, than in songs written after 1990. In fact, the percentage of songs referencing God at least ten times is at its highest in songs written after 2000. In other words, songs written in the last 20 years show a propensity for either not naming God at all or naming Him in abundance.

As mentioned before, while direct names of God were used for this tabulation, there are instances of references to God without direct names for God. However, even with that tabulation entered, there are still 21 songs that have no reference to God, other than pronoun usage. These songs are listed in figure 1. As this song list shows, 20 of the 21 songs were written after 1990. These songs could be referred to as the “Jesus is my boyfriend” songs, since there is no direct reference to the person being addressed.

- When I Look Into Your Holiness (1981)

- Draw Me Close (1994)

- Breathe (1995)

- In the Secret (1995)

- Above All (1999)

- Be Glorified (1999)

- The More I Seek You (1999)

- Here We Are (2000)

- Grace Like Rain (2003)

- I Am Free (2004)

- How He Loves (2005)

- Your Love Never Fails (2008)

- I Will Follow (2010)

- One Thing Remains (2010)

- You Are Good (2010)

- Lay Me Down (2012)

- It Is Well (2013)

- Come As You Are (2014)

- Fierce (2015)

- Your Love Awakens Me (2016)

- Stand in Your Love (2018)

Figure 1. Songs from the Main Corpus with No Direct Reference

With regard to the referencing of God, it is important to look not only at the number of songs that use pronouns or direct names for God, but also at the number of times each type of pronoun or direct naming of God is used compared to the total number of God references. Table 4 presents the percentage of second-person pronouns, third-person pronouns, and direct names of God, compared to the total number of God references in all the songs from each time period. There are several notable results from this analysis. First, the percentage of “you” pronouns accounts for more than half of all references to God in songs written after 1990, compared to 16% in songs prior to 1970. Conversely, the number of “he” pronouns decreases substantially in songs written after 1990, as does the percentage of direct names of God. The songs by the Gettys follow closely to traditional hymnody, while Sovereign Grace follows closely to contemporary lyric practices.

Table 4. The Percentage of Pronouns or Direct Names of the Godhead Compared to the Total Number of References to God

| Psalms | <1970 | 1970–1989 | 1990–1999 | 2000–2009 | 2010–2018 | Gettys | Sov. Grace | |

| 2nd Per./ All | 31.0 | 16.0 | 29.0 | 57.0 | 48.0 | 53.0 | 21.0 | 51.0 |

| 3rd Per./ All | 24.0 | 30.0 | 23.0 | 9.0 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 27.0 | 16.0 |

| Names/ All | 42.0 | 42.0 | 39.0 | 28.0 | 31.0 | 28.0 | 43.0 | 29.0 |

| % of: | 150 Psalms | 140 songs | 60 songs | 50 songs | 68 songs | 88 songs | 50 songs | 50 songs |

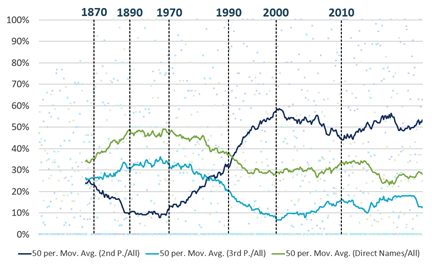

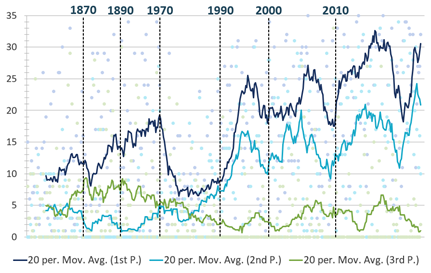

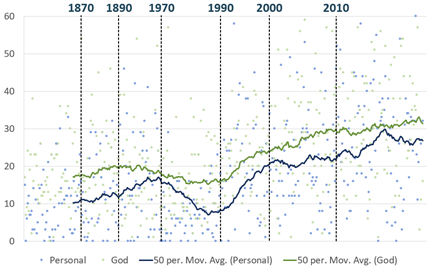

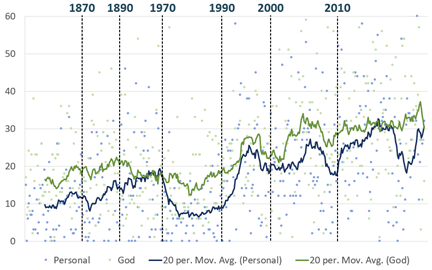

Figure 2a provides a timeline of the main corpus (406 songs) from the previous table, with trendlines showing the averages. The dark blue line designates second-person pronouns, the light blue line designates third-person pronouns, and the green line designates direct names. As this figure highlights, using a 50-song moving average, the transition period occurs between 1970 and 1990, and continues much the same way after 1990. However, by changing the moving average to 20 songs, as shown in figure 2b, there is a more nuanced picture of these changes. For instance, songs prior to 1870 in the corpus shared a similar percentage for each of the categories. Songs between 1870 and 1970 provided a general consensus of direct names were the highest average, while second-person pronouns being the lowest average. While the years 1970–1990 still show the transition period, there are some oscillations in the data after 1990. For instance, the use of direct names reaches its lowest point in the mid-2010s, while the third-person pronouns reach their highest point since 1990. Also, the use of second-person pronoun usage spikes in the mid-1990s as well as in the early and late 2010s. There are a couple of times, however, that the use of second-person pronouns drops below the use of direct names for God, particularly around 2010 and in the mid-late 2010s. Thus, while the larger picture shows the general trend, there are some smaller-scale shifts in God references in the last 40 years.

Figure 2a. Trendlines Showing the Percentages of Point of View References to God in Songs of the Main Corpus Over Time (50-song moving average)

Figure 2b. Trendlines Showing the Percentages of Point of View References to God in Songs of the Main Corpus Over Time (20-song moving average)

Analyzing Personal References

The second focus of the corpus analysis is on the use of personal references. There are two possible uses of personal pronoun references. One is the singular first person (I, me, my, mine), which focuses on the individual singing. The other is the plural first person (we, us, our), which focuses on the corporate body singing the song. Table 5 presents the percentage of songs that utilize either first person singular pronouns, first person plural pronouns, both singular and plural, or neither. It is interesting to note that 18% of the Psalms do not have a first-person pronoun in them. These Psalms are not focused on first-person man at all, but rather outwardly to others and to God solely. While around 10% of songs prior to 1990 are also solely God-focused, that number drops substantially to only 2% of songs after 1990. Another interesting observation is that while first-person singular pronouns range from 60 to 80%, and first-person plural pronouns range from 35 to 50% of songs in the main corpus and Psalms, the songs by the Gettys fall way outside these averages in both cases.

Table 5. Percentage of Songs that Reference Man, Using Singular or Plural Pronouns, or Both

| Psalms | <1970 | 1970–1989 | 1990–1999 | 2000–2009 | 2010–2018 | Gettys | Sov. Grace | |

| Neither | 18.0 | 9.3 | 11.7 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 4.0 | 0.0 |

| Singular | 68.9 | 60.0 | 61.7 | 80.0 | 73.5 | 72.7 | 46.0 | 64.0 |

| Plural | 40.0 | 45.0 | 43.3 | 34.0 | 50.0 | 52.3 | 84.0 | 56.0 |

| Both | 26.0 | 14.3 | 16.7 | 18.0 | 25.0 | 27.3 | 34.0 | 20.0 |

| % of: | 150 Psalms | 140 songs | 60 songs | 50 songs | 68 songs | 88 songs | 50 songs | 50 songs |

The Getty songs use first person singular pronouns in less than half of the songs in the corpus, while first-person plural pronouns are found in 84% of those songs. These statistics are strikingly different than all other categories, and highlight the songwriters’ focus on “corporate” singing. Figure 3 presents the songs in the main corpus (excluding Gettys and Sovereign Grace) that do not use a first-person pronoun in the song. Several of the songs address other individuals, even shown in the title using second-person pronouns, but the song is focused outward, rather than inward.

- Praise God from Whom All Blessings Flow (1551)

- Stand Up, Stand Up for Jesus (1830)

- Joy to the World (1848)

- It Came Upon a Midnight Clear (1850)

- Only Trust Him (1874)

- Are You Washed in the Blood (1878)

- America, the Beautiful (1882)

- Blessed Be the Name (1887)

- Count Your Blessings (1897)

- There Is Power in the Blood (1899)

- God Will Take Care of You (1905)

- Thou Art Worthy (1963)

- Seek Ye First (1972)

- Ah, Lord God (1976)

- Let There Be Glory (1978)

- There’s Something About that Name (1979)

- Majesty (1981)

- Come into His Presence (1983)

- No Other Name (1988)

- Agnus Dei (1990)

- Ancient of Days (1992)

- Come As You Are (2014)

- O Come to the Altar (2015)

Figure 3. Songs from the Main Corpus with No Singular Pronoun References to Man

In addition to looking at the percentage of songs utilizing first person pronouns, the analysis included examining the number of times pronouns were used in each song. This again involved looking at the form of the song and tabulating each type of pronoun based on how many times it would be sung in a repeated passage. Table 6 shows the average number of times a category of pronouns was sung in each song within a time period. The asterisks in the Psalms column indicate that these averages are based on the Hebrew text, since that is ultimately the number of times each category of pronouns is used (unlike the percentage of each category used in total, which stays almost the same between the original Hebrew and the English translations). As the table shows, the use of first-person singular pronouns dramatically increases in songs after 1990 in the main corpus, as does the use of first-person plural pronouns. Traditional hymnody follows very closely to the word averages of the Psalms. At the same time, the use of second-person pronouns for God (you) increases even more dramatically, more than five times the amount from songs prior to 1970 to songs after 2010. Here, however, the Psalms sit roughly in the middle. Finally, while the use of third-person pronouns decreases over time by roughly half, the use of God references actually increases slightly over time.

Table 6. Average Number of References to Man and God in Songs from Each Category

| Psalms | <1970 | 1970–1989 | 1990–1999 | 2000–2009 | 2010–2018 | Gettys | Sov. Grace | |

| 1st

Person Singular |

10.41* | 10.21 | 5.23 | 18.90 | 16.40 | 20.17 | 5.82 | 10.98 |

| 1st

Person Plural |

1.68* | 2.76 | 2.75 | 1.72 | 5.00 | 7.35 | 6.00 | 6.58 |

| 2nd Person God | 8.91* | 3.14 | 5.13 | 13.32 | 14.13 | 17.49 | 4.22 | 12.76 |

| 3rd Person God | 6.43 | 6.28 | 3.32 | 2.28 | 3.59 | 3.13 | 4.90 | 5.86 |

| Reference

to God |

8.61 | 8.66 | 7.88 | 8.56 | 11.06 | 10.36 | 9.74 | 8.84 |

| Out of: | 150 Psalms | 140 songs | 60 songs | 50 songs | 68 songs | 88 songs | 50 songs | 50 songs |

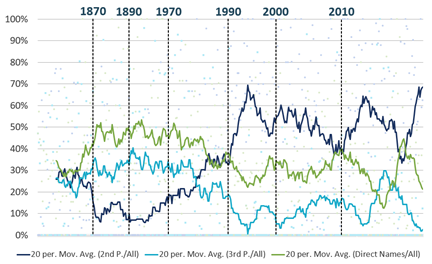

Figure 4a represents the average usage of first-person (man), second-person (God), and third-person (God) pronouns over time. As the figure shows, the use of first-person pronouns (dark blue line) actually increased between 1870 and 1970, before dropping significantly from 1970 to 1989. Figure 5 presents a list of selected songs from the main corpus that were written from 1970 to 1989, all which reflect a sharp decrease in use of first-person pronouns and an increase in use of third-person pronouns. This dramatic change coincides with the rise of the charismatic movement in America, as well as the Jesus movement within the evangelical community. However, after 1990, the use of first-person pronouns increases significantly, reaching an average of 30 times per song by the mid-2010s. This is three times the number of uses of first-person pronouns than in songs prior to 1870. While the use of first-person pronouns increases significantly after 1990, the use of second person (God) pronouns also significantly increases. Conversely, the use of third-person pronouns decreases during that time. The significant rise of second-person pronouns for God in songs after 1990 indicates a shift in the view of God in song lyrics. Songs tend to focus on the personal aspect of God, his immanence to man, rather than his transcendence and distance from man. The increased use of “you” pronouns also can have the effect of clouding the object of who one is singing to, especially if there is no direct name for God, or it comes late in the song. Figure 4b presents the same data, but with a moving average of 20 songs instead of 50 songs. This graph shows the stark contrast in first person pronouns between songs prior to 1970, the drastic drop from 1970 to 1990, and the even more drastic increase after 1990.

Figure 4a. Trendlines Showing the Number of Instances of Point of View Pronouns in Songs of the Main Corpus Over Time (50-song moving average)

Figure 4b. Trendlines Showing the Number of Instances of Point of View Pronouns in Songs of the Main Corpus Over Time (20-song moving average)

- Jesus, Name above All Names (1974)

- Emmanuel (1976)

- Praise the Name of Jesus (1976)

- All Hail, King Jesus (1981)

- How Majestic Is Your Name (1981)

- Majesty (1981)

- Great is the Lord (1982)

- There is a Redeemer (1982)

- He is Exalted (1985)

- Worthy, You are Worthy (1986)

- No Other Name (1988)

Figure 5. Selected Songs from 1970 to 1989 in the Main Corpus

Analyzing the Balance of Focus between God and Man References

Finally, the lyrical analysis includes a look at the balance of focus between God and man in each of the songs/Psalms. Here, the research is based on a simple formula used in Daniel Thornton’s dissertation. In explaining his notion of “balance of focus,” Thornton states:

It is not only the point of view [POV] that is relevant, but how much of the personal (singular or plural) perspective is referenced compared with the song’s terms of address to the Godhead. . . . After counting the number of POV references, and the number of Godhead address references, a fraction was created. If the number of POV references was greater than the number of address references, then the fraction would be greater than 1, and would represent a singer-focused song rather than a God-focused song for a fraction of less than 1.[11]

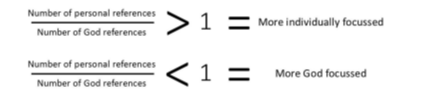

Figure 6 shows a visual representation of the Godhead versus man point of view fraction. As shown, any number over 1 is considered man-focused, while any number under 1 is considered God-focused.

Figure 6. Visual Representation of Godhead and Point of View fraction

Table 7 shows the percentage of songs in each time period, based on the balance of focus for each song. The middle three rows add up to 100% of songs in each time period, while the outer rows indicate the percentage of songs that are at least doubly God or man focused. There are several interesting findings in this analysis. First, the most God-focused time period of songs, by far, is 1970–1990, followed by 2000–2009. Part of the reason that songs prior to 1970 are lower is the fact that songs after 1870 become much more man-focused. Second, the most man-focused time period is nearly tied between 1990–1999 and 2010–2018. Third, the Psalms are more God-centered than the main corpus time periods, other than the 1970s–80s, and more than half the Psalms reference God at least twice as many times as man. None of the other time periods are that doubly God-focused. Finally, in contrast to the main corpus, the Gettys and Sovereign Grace songs are much more God-focused, with over 75% of their songs referencing God more than man.

Table 7. The Percentage of Songs and Their Balance of Focus between God References and Man References in Each Category

| Psalms | <1970 | 1970–1989 | 1990–1999 | 2000–2009 | 2010–2018 | Gettys | Sov. Grace | |

| Over 2 | 8.0 | 10.7 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 19.1 | 10.2 | 6.0 | 4.0 |

| Over 1 | 29.3 | 32.9 | 8.3 | 44.0 | 33.8 | 44.3 | 22.0 | 20.0 |

| 1 | 2.0 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 6.0 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| Under 1 | 68.7 | 60.7 | 85.0 | 50.0 | 66.2 | 52.3 | 74.0 | 76.0 |

| Under .5 | 53.3 | 37.9 | 48.3 | 26.0 | 36.8 | 23.9 | 44.0 | 32.0 |

| % of: | 150 Psalms | 140 songs | 60 songs | 50 songs | 68 songs | 88 songs | 50 songs | 50 songs |

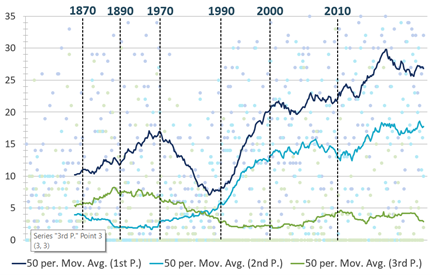

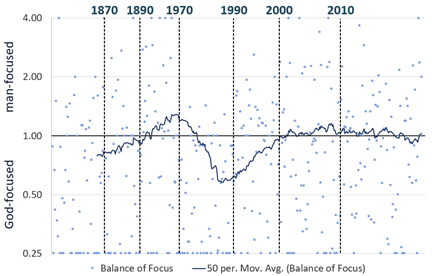

Following the previous analyses, Figure 7a presents the main corpus data in chronological order, showing trends over time, using a 50-song moving average. This figure highlights the fact that the balance of focus in congregational songs has actually shifted back and forth over time. The period 1870–1970 shows a shift from more God-focused songs to more man-focused songs. In fact, from 1890 to 1970, the graph presents the most man-focused song average than any other period, including today. This actually refutes the notion that songs today are more “me-focused” than ever before. The period from 1970 to 1990 again shows an abrupt shift, with the balance of focus shifting back to God-focused. After 1990, however, the balance of focus shifts back to man-centered, a trend that has stayed roughly the same for the past 30 years.

Figure 7a. Trendlines Showing the Balance of Focus between God References and Man References in Songs of the Main Corpus Over Time (50-song moving average)

Figure 7b uses a moving average of 20 songs instead of 50 songs to provide a more nuanced picture of the shifting balance of focus over time. For instance, the period 1890–1970 shows a steadier man-focused average, and the shift at 1970 is even more abruptly to God-focused songs than the previous graph indicated. The shift back to man-focused songs is also more abrupt after 1990. Also, there are several points in the last 30 years that the songs written tended toward more God-focused than man-focused, as indicated with the trendline bouncing back and forth around the line of demarcation. As the very end of the trendline shows, however, the shift has been quite steady toward man-focused songs in that last couple of years.

Figure 7b. Trendlines Showing the Balance of Focus between God References and Man References in Songs of the Main Corpus Over Time (20-song moving average)

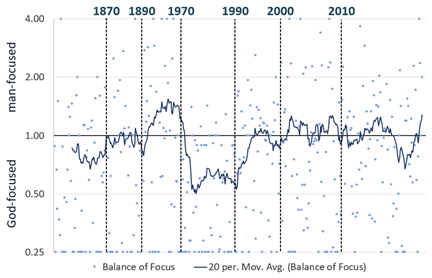

The reason that the balance of focus has not dramatically shifted to man-centered songs in recent years, despite the increased number of “man” references in the songs, is that there is an almost equal increase in the number of God references in those same songs, which is depicted in figure 8a. For instance, when viewing the trend over time of the number of personal references to the number of God references, the two lines tend to decrease and increase at similar intervals. With a more nuanced trendline in figure 8b, showing a 20-song moving average, there are a couple of times when the personal references overtook the number of God references, specifically at around 1900–1970, and again during the mid-2010s, and even currently. This recent trend is probably what people are referring to when saying that songs are so me-centered in worship today.

Figure 8a. Trendlines Showing the Number of Man References and God References in Songs of the Main Corpus Over Time (50-song moving average)

Figure 8b. Trendlines Showing the Number of Man References and God References in Songs of the Main Corpus Over Time (20-song moving average)

While these figures present the general trends in groups of songs over time, the corpus analysis is not arguing that singing a man-focused congregational song is somehow less praiseworthy than singing a God-focused song. There are plenty of excellent man-focused songs written over the years. For instance, figure 9 list songs in the corpus with a fraction larger than four, which means that they have at least four times as many man references as they do God references. In looking at the list, six of the 11 songs were written between 1869 and 1932, the period of time when the trendline shifts to more man-focused songs. However, these songs are still theologically sound and display a richness for thinking about our place before God. The point is not to disparage the use of man-focused songs, but to understand that there needs to be a balance between focusing on man versus focusing on God. If we only sing man-focused songs, we miss out on truly focusing our attention on and our position to the subject of our worship, which is the Triune God.

- The Star-Spangled Banner (1814)

- Jesus Keep Me Near the Cross (1869)

- Alas and Did My Savior Bleed—Hudson (1885)

- Amazing Grace (1900)

- A New Name in Glory (1910)

- The Old Rugged Cross (1913)

- I’ll Fly Away (1932)

- Ancient Words (2001)

- Grace Like Rain (2003)

- I Heard the Bells (2008)

- Raise a Hallelujah (2018)

Figure 9. Songs of the Main Corpus That Are at Least 4x Man-Focused

Conclusion

As the preceding corpus analysis has shown, there have been several changes within lyrical content of congregational songs over time. With regard to referencing God, there has been an increase in the number of songs that do not directly name God, specifically after 1990. At the same time, songs after 1990 have significantly increased the use of the personal pronoun “you” when referring to God, in that over 50% of the references to God in those songs are with second person pronouns. With regard to personal references, there has been a two-fold increase in the number of personal references between songs written prior to 1970 and songs written after 1990. Finally, in looking at the balance of focus in songs, there have been several shifts back and forth between man-focused and God-focused songs over time. Ultimately, this research offers clarity and precision to the discussion of those textual changes in congregational songs. It is intended to show some of the nuances of these changes in order to help worship leaders understand and take seriously the role of selecting songs for corporate singing. This role includes studying the lyrics and examining the balance of focus between God and man in each song being sung. We need to be ever mindful of the subject of our worship, which is God. As believers, we are not the subject of worship, and any song that puts the focus on man without properly aligning that focus to the true subject of worship, God, should not be considered for corporate worship of God. It should be the goal of every worship leader to choose songs that express these truths, and this research hopefully helps shed light on some of the issues to consider when selecting appropriate songs for corporate worship.

[1] Nathan Burggraff, PhD, is assistant professor of music theory and director of the music theory and piano departments at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary.

[2] Robert Webber, The Divine Embrace: Recovering the Passionate Spiritual Life (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2006), 231–32.

[3] Webber, The Divine Embrace, 232–33.

[4] See Lester Ruth, “Some Similarities and Differences between Historic Evangelical Hymns and Contemporary Worship Songs,” Artistic Theologian 3 (2015): 68–86; Daniel Thornton, “Exploring the Contemporary Congregational Song Genre: Texts, Practice, and Industry” (PhD diss., Macquarie University, 2015); and Stuart Sheehan, “The Changing Theological Functions of Corporate Worship among Southern Baptists: What They Were and What They Became (1638–2008)” (PhD diss., University of Aberdeen, 2017).

[5] Thornton, “Contemporary Congregational Song Genre.”

[6] The main corpus, made up of 406 songs, is a combination of CCLI’s Top 100 Songs (June 2016–2019), CCLI’s 100 Most Popular Public Domain Songs (June 2016–2019), CCLI’s semi-annual Top 25 song lists (1989–2015; from Lester Ruth’s 2015 article), PraiseCharts Top 100 Worship Songs of All Time (2018), Hal Leonard’s “The Best Praise & Worship Songs Ever” (2004), and Hal Leonard’s “More of the Best Praise & Worship Songs Ever” (2018). Two additional corpuses were created from CCLI’s Top 50 Gettys Songs and CCLI’s Top 50 Sovereign Grace Songs, since both groups are scarcely represented in the other ranked lists, but are sung in many churches in America.

[7] The tabulation of the Hebrew pronouns was performed using a search and find function in Logos Bible Software.

[8] Mark Evans, Open Up the Doors: Music in the Modern Church (London: Equinox Publishing Ltd., 2006).

[9] Evans, Open Up the Doors, 165.

[10] John Fischer, On a Hill Too Far Away: Putting the Cross Back into the Center of Our Lives (Minneapolis, MN: Bethany House, 2001), 52–53.