Does God Inhabit the Praises of His People? An Examination of Psalm 22:3

Artistic Theologian 8 (2020): 5–22

Matthew Sikes is a Church Music and Worship PhD student at Southwestern Seminary and Pastor of Discipleship and Worship at Pray’s Mill Baptist Church in Douglasville, GA.

“God inhabits the praises of his people.” In recent years church leaders across a broad spectrum of Christianity have commonly encouraged their churches with this exhortation. This phrase is often presented as an encouragement for congregants to intensify their participation in the gathering so that they may further experience God’s tangible presence. Yet, clarity must be sought in understanding the meaning of this phrase and its context in Scripture.

Further investigation into the use of this expression and its origins reveals Psalm 22:3 as the source. The King James Version renders this verse as: “But thou art holy, O thou that inhabitest the praises of Israel.” Others translate it more like the NIV: “Yet you are enthroned as the Holy One; you are the one Israel praises.” Just a cursory glance at these two different renderings begins to reveal some of the ambiguity in translating this text. Beyond issues of translation arise matters of exegesis and hermeneutics.

The purpose of this paper is to examine Psalm 22:3 in its canonical and historical context to give an Old Testament framework for understanding God’s enthronement and presence in corporate worship and to provide implications for the practice of worship in a new covenant setting. Furthermore, my aim in writing stems from a desire to uncover a biblically faithful interpretation and application of a passage that has frequently been cited to overemphasize the responsibility of the worshiper in corporate gatherings. A survey of the works of many prominent writers of previous decades reveals the evident belief that God is present in a different way because of his people’s praises.[2]

This study opens with a synthesis of contemporary applications of Psalm 22:3 as found mostly within the Pentecostal and Charismatic movements. I will then present an exegesis of this passage, beginning broadly with the Psalms and narrowing to verse three in its context, leading to an examination of the Old Testament concept of God’s enthronement as it relates to his presence. Finally, I will provide implications for the use of Psalm 22:3 in the context of contemporary worship under the new covenant. Throughout this paper I argue that although many modern Christians have understood God’s enthronement on the praises of his people as an anthropocentric idea of man’s responsibility in worship, a more faithful interpretation emphasizes God’s sovereign rule and reign over his covenant people as the central theme of Psalm 22:3.

Contemporary Interpretations

In her book Extravagant Worship, Darlene Zschech contends:

The Word says that God inhabits the praises of his people (Psalm 22:3). It’s amazing to think that God, in all his fullness, inhabits and dwells in our praises of him. . . . Our praise is irresistible to God. As soon as he hears us call his name, he is ready to answer us. That is the God we serve. Every time the praise and worship team with our musicians, singers, production teams, dancers, and actors begin to praise God, his presence comes in like a flood. Even though we live in his presence, his love is lavished on us in a miraculous way when we praise him.[3]

This quotation appears to reveal the common notion that Psalm 22:3 should be interpreted as a command for man’s responsibility to praise so that God’s presence will be made manifest. However, as I will argue below, this interpretation is unlikely. The pervasiveness of this viewpoint necessitates an exploration into the history of how this interpretation came into contemporary usage.

In their work Lovin’ on Jesus: A Concise History of Contemporary Worship, Swee Hong Lim and Lester Ruth find the origins of this interpretation with the Pentecostal emphasis on “a priority for praise as the central activity of an assembled congregation.” Lim and Ruth argue that this “priority for praise” emerged in the Canadian Latter Rain Revival of the mid-twentieth century and with Pentecostal preacher Reg Layzell, who pointed specifically to Psalm 22:3 as a proof-text.[4] The idea of praise as a separate, although related, activity from worship developed in the writings of prominent Pentecostal and Charismatic authors in the decades that followed. In the 1970s, author Judson Cornwall wrote about his revelation that “the path into the presence of God was praise.”[5] He published a follow-up work in the 1980s in which he cited his discovery that praise and worship were in fact two distinct and progressive activities.[6] In 1987 Bob Sorge wrote in a similar vein as he discussed the priority for praise and the distinction between praise and worship,[7] and in 1994 Terry Law wrote How to Enter the Presence of God, which similarly highlighted this distinction.

Moreover, along the way these authors began to associate the ideas of praise and worship exclusively with music and included thanksgiving as a prerequisite to both. Likewise, in the 1980s “praise and worship” became a “technical term outlining a biblical order for a service: first thanksgiving, then praise, and then worship.”[8] Reliance upon Psalm 100:4 became a critical component in developing this music-centered order of worship. Lim and Ruth state:

By the early 1980s this step had been taken and, in an important move, was interpreted in a musical way. Thanksgiving, praise, and worship became a way of envisioning the ordering of songs in the time of congregational singing. The emerging biblical theology had been musicalized.[9]

Praise and worship became a fully developed liturgical phenomenon, and music was the primary tool used to express the liturgical movement.

Referencing Psalm 22:3 and 100:4, Lim and Ruth contend that “together the two passages established a strong sense that God’s presence could be experienced in a special way through corporate praising and that sequencing acts of worship in a certain way could facilitate the experiencing of divine presence and power.”[10] This statement represents the idea that the emphasis had now been placed on man’s responsibility in corporate worship to praise God and its causal relationship to the direct and tangible experience of God’s presence. The musical choices made by leaders of the congregation were thought to be the primary tool for the manifestation of God’s presence.

The connection that has evolved between music and the praise and worship liturgy is so pervasive that Lim and Ruth see music as becoming a new sacrament in the practice of those within the Pentecostal and Charismatic movements. In fact, the chief musician of the church was no longer referred to as the “song leader,” as was prevalent in the early days of Pentecostalism, but the title had shifted to “worship leader” by the 1980s. As Barry Griffing argues, “the goal of the worship leader is to bring the congregational worshipers into a corporate awareness of God’s manifest Presence.”[11] Praise, worship, and music became so closely intertwined that books like God’s Presence through Music were written to give direction on how to employ ideal tempo, key, and lyrical content for God’s presence to be made manifest.[12] As Lim and Ruth argue, “a worship leader’s job was to ‘make God present through music.’ The sacrament of musical praise had been established.”[13]

Eventually, for many reasons, many of these teachings began to invade the broader world of Evangelicalism. In 1991 Reformed Worship magazine dedicated an entire issue to the Praise and Worship phenomenon in which influential worship scholar Robert Webber wrote an article explaining the origins of the praise and worship movement and defining some of its qualities. In this article Webber cites many of the same sources that Lim and Ruth provide. One quotation that he submits from John Chissum further elucidates the sacramentality of music that developed:

John Chisum, Vice President of worship resources at Starsong Communications in Nashville, describes the third phase of the sequence [in the praise and worship liturgy] as an experience of “the manifest presence of God.” He says this experience does not differ greatly from the liturgical experience of the presence of Christ at the Lord’s table. “In this atmosphere,” he claims, “the charisma, or gifts of God are released.” And “just as many throughout the history of the church have experienced physical and spiritual healing while partaking of the body and blood in the elements of the table of Christ, so many today are tasting of special manifestations of the Holy Spirit in worship renewal as he inhabits, i.e. settles down, makes his home and abides, in the praises of his people.”[14]

The reference to Psalm 22:3 is once again evident in this statement.

Perhaps the composition of this article and others like it by prominent mainline theologians could have contributed to some level of adaptation of the praise and worship model. In his closing lines Webber writes, “what I see in the future is a convergence of worship traditions, a convergence of the liturgical, traditional nonliturgical, and the Praise and Worship tradition. It does not seem to me to be an either/or, but a both/and.” This understanding of worship is evident in many churches today.

Interpreting Psalm 22:3 In Context

In light of this recent interpretation, I will now attempt to uncover the meaning of Psalm 22:3 in its exegetical, historical, and canonical context. I begin by examining some general issues in interpreting the Psalms, providing an overall framework and addressing some of the literary nuances contained within the Psalms, allowing for a more detailed exegesis of Psalm 22, which will provide parameters for a more faithful interpretation of verse three.

General Overview for Interpreting the Psalms

Interpreting the Psalms, especially from a new covenant vantage point, necessitates a theological framework that recognizes the purpose of the psalms in their original context and placement within the canon. Only after establishing this framework is it possible to more fully understand their application within the new covenant. I will briefly present some pertinent concepts that clarify the interpretation of Psalm 22.

First, conservative scholars generally agree that the Psalter reached its final form after the return of the Israelites from exile;[15] yet writing of the Psalms clearly spans many centuries of the Old Testament.[16] Thus, while the historical context of the Psalms is certainly important, their theological context within the history of Israel has greater significance. Mark Futato explains the purposeful use of universal and general language within the psalter, which would have had universal meaning for the people of Israel in the context of their worship. That same use of general and universal language assists worshipers in a new covenant context because this “lack of precision in . . . understanding of the historical context of a given psalm results in increased ease in applying the text to contemporary life.”[17]

Identifying the original purpose of the Psalms raises a second issue. Sigmund Mowinckel indicates that “the title of the book of Psalms in Hebrew is Tĕhillîm, which means ‘cultic songs of praise.’ This tallies with the indications we have that songs and music of the levitical singers belonged to the solemn religious festivals as well as to daily sacrifices in the Temple.”[18] Praise is a dominant theme of the Psalms; however, readers will have difficulty reading the Psalms and missing the extensive presence of lament. Longman helps to elucidate this fact by stating that “a decided shift takes place” from the beginning of the psalter to the end, generally moving from lament to praise: “In a real sense, the book of Psalms moves us from mourning to joy.”[19]

Finally, having a framework for interpreting Hebrew poetry is necessary, for without this the reader will have great difficulty adequately understanding and applying the Psalms. Many of the severest interpretive errors are made because of a lack of basic understanding of Hebrew poetry. The two categories of necessary interpretation are parallelism and imagery.[20]

Interpreting Psalm 22

While initial readings of psalms do not always provide easy categorization, the tone of Psalm 22 is unmistakable, especially within its first 21 verses. In fact, the first two verses establish that this is a psalm of lament, using phrases like, “why have you forsaken me? Why are you so far from saving me? . . . you do not answer,” and “I find no rest.” Any Christian reading this psalm would most assuredly be reminded of the words of Christ as he is dying on the cross. However, as Ross states, this psalm must “be read first in the suffering psalmist’s experience as an urgent prayer to be delivered from enemies” before it can be read in its messianic context.[21]

Upon deeper inspection, some objection may be plausible in categorizing this psalm as one of lament. Division in two parts is found at the macro level—verses 1–21 and verses 22–31. Strikingly, these two parts seem to lie in stark contrast. Verse 22 provides a decided shift in the author’s tone—from agony and grief to deliverance and thanksgiving. Ross posits that a typical psalm of lament would end with a vow to praise; however, “where the vow of praise would normally be [one finds] the main features of a declarative praise psalm.”[22] This psalm provides a vivid example of the aforementioned concept that the Psalms generally move from lament to praise.

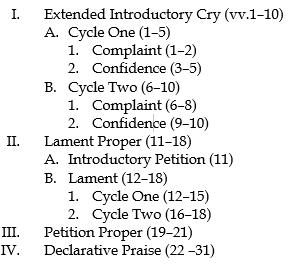

The basic structure of this psalm based on Allen Ross’s exegetical outline is as follows:

Historically, difficulty arises when determining the exact context of this psalm. The indication that this is a psalm of David could either signify a composition by David or in the style of David by a later author. While this appears to be an individual psalm of lament,[23] clearly the psalmist also considers his perspective as a member of the covenant community, switching between the usage of first person singular and plural pronouns. Irrespective of composition date, the text appears to indicate an awareness and intention for use in public worship that would be further confirmed by postexilic psalter use in temple worship.[24]

More specifically, the above outline elucidates the two cycles of complaint and confidence that occur within the first ten verses. Realization of this cycle provides two greater points for the purposes of this study. First, the move from complaint to confidence is a foreshadowing of the shift that will take place in verse twenty-two. Second, and more significantly, the first section of confidence begins with the verse in question for this paper—verse three.

Putting Verse Three in Context

In many ways, verse three is one of the more difficult to translate and interpret in Psalm 22. Three primary issues arise—translating and interpreting the parallelism, the meaning of the Hebrew word yashab (“inhabitest,” KJV), and understanding the poetic imagery being employed.

The psalmist is drawing an obvious contrast in verse three as he begins the sentence with “yet you” or “but you.” VanGemeren states:

The pronoun “you” (v 3) is emphatic and, together with the contrastive use of the connective participle, sets up the distance between God and the psalmist: “Yet you” (“But you”). One may venture to say that he feels a tension in his experience with God (“my God,” three times) and in God’s dealings with Israel.[25]

The psalmist is contrasting what he is experiencing with the reality of what he knows of God and his character. God is holy and enthroned on the praises of Israel. The author knows this not only as an abstract theological concept, but he knows it experientially, recalling the trust of God and subsequent deliverance by the psalmist’s ancestors.[26] God’s holiness and enthronement are past, present, and future realities.

The issue of interpreting the parallelism manifests itself in two remarkably different ways. The NIV translates verse three as “Yet you are enthroned as the Holy One; you are the one Israel praises,” while the ESV renders it “Yet you are holy, enthroned on the praises of Israel.” The reason for this variation lies with how readers are to interpret the division of the cola.

This line from the psalm is a bicolon that must be divided into two parts. There is historic debate in dividing the cola with the five Hebrew words in the verse, whether they should be broken into 2 + 3 or 3 + 2, and with which colon the Hebrew wor yashab belongs. The NIV follows the 3 + 2 division, and the ESV and KJV follow a 2 + 3 division. The most prominent reason for debate originates with the Septuagint translation of the passage, which, when translated into English, renders the verse, “But you, the praise of Israel, dwell in a sanctuary/among saints.”[27] Goldingay provides some clarity on this issue:

I follow the LXX and Jerome in understanding v. 3 as 3–2 rather than 2–3, which would imply, “But you are the holy one, enthroned on/inhabiting the great praise of Israel” (cf. KJV; NRSV; BDB). The idea of Yhwh’s sitting enthroned in the heavens or in Zion is a familiar one (2:4; 55:19 [20]; 80:1 [2]; 99:1; 123:1; cf. 99:1–3 for the association with Yhwh’s being the holy one; also Isa. 57:15). Likewise, the idea that Yhwh is Israel’s praise is a familiar one (Deut. 10:21; Jer. 17:14), but the idea of Yhwh’s being enthroned on or inhabiting Israel’s praise is unparalleled, and if either of these is the psalm’s point, one might have expected it to be expressed more clearly. The fact that 3–2 is the more common line division supports the conclusion that LXX construes the line correctly.[28]

Goldingay believes that the best way to interpret the verse is to use the 3 + 2 division, following the Septuagint. Furthermore, his position that the Israelites and the translators of the Septuagint would have had difficulty with the concept of the LORD’s dwelling in the actual praises of Israel is confirmed by Ross.[29] However, in contrast to Goldingay’s translation, Ross believes the correct division is 2 + 3 and translates it as “But you are holy, you who are enthroned in the praises of Israel.”[30] Yet Ross sees no inconsistency with holding the position that the concept of the LORD as dwelling in the actual praises of Israel would have been foreign to ancient Israelites. His clarification comes with a proper hermeneutic of poetic imagery, a matter addressed below.

The next two issues are related; however, I will address them separately for clarity. The Hebrew word yashab and its derivatives are used 1090 times in the Old Testament.[31] The word can, of course, communicate many meanings based on context, including “sit,” “dwell,” “inhabit,” “enthrone,” or even “tabernacle,” and it is used of both God and men. Both translations already given, “enthroned” and “inhabits,” are appropriate in the context of this passage. However, the concern for contextual interpretation remains and will be addressed below.

Finally, if the reader follows the 2 + 3 cola division, then the question of how to interpret the meaning of God’s enthronement on the praises of Israel remains. First, the psalmist recognizes and calls attention to God’s holiness, and this is important for the context of what follows. Again, recalling the cycle here of complaint and confidence, worshipers should recognize the LORD’s holiness in opposition to the psalmist’s plight. “Enthroned on the praises of Israel” is a statement that qualifies or elaborates on the reality of God’s holiness. Ross sees God’s holiness signifying his very essence; God is different, set apart, and completely other than anyone or anything else. This is especially true in relation to the pagan gods of the surrounding nations. “To say God is holy in the midst of a lament about unanswered prayer means that God is not indifferent or impotent like the pagan gods—he is different; he has power; and he has a history of answering prayers.” Ross continues,

In the context, then, this attribute of God’s holiness is appropriate for building confidence. The rest of the verse builds on this general description for the immediate need: God is so faithful in answering prayer that his people are constantly praising him in the sanctuary. To express this the psalmist describes God as one who sits enthroned in their praises (a metonymy of adjunct, “praises” meaning the sanctuary where the praises are given). The praises are so numerous that God is said to sit enthroned on them. God was obviously answering prayers.[32]

Understanding this poetic device—metonymy of adjunct—is key to proper interpretation of the verse. Ross defines the metonymy of adjunct as a figure of substitution where “the writer puts the adjunct or attribute or some circumstance pertaining to the subject for the subject itself.”[33] Various metonymic devices are commonly found throughout the Psalms and Old Testament.[34] Similarly, the Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament, in its entry on the Hebrew word yashab, cites this very passage as a “metonymy for the sanctuary where the Lord was praised.”[35]

Implications from the Exegesis of Psalm 22:3

Thus far I have shown the necessity of approaching a psalm with a proper understanding of genre, context, and purpose. I have provided a means for gaining greater clarity on how to interpret Psalm 22 as a psalm of lament, which has a drastic shift toward praise of the LORD in its final verses. Finally, I have provided two explanations for how to interpret verse three specifically. If Goldingay and translations like the NIV and LXX are correct in the way that the parallelism is divided (3 + 2), then the interpretation is clear, and no further clarification should be needed. Contrastingly, if Ross and others are correct in their position, that the division of the bicolon should be 2 + 3, then the “praises of Israel” is best understood as a representative for the LORD dwelling in the sanctuary or the temple where the praises of Israel took place. Examining the concept of God’s presence through his “dwelling” and “enthronement” in the Old Testament will provide greater clarity.

God’s Enthronement in the Old Testament

God’s enthronement focuses on his sovereign reign and authority over his covenant people and all of creation. The theme of God’s kingship is woven throughout Scripture. Nowhere is this more prevalent than in the book of Revelation, which paints a picture of the telos of all God’s redeemed as well as all the heavenly beings worshiping around the throne of God. In some way, every book in the Bible is pointing to this final and ultimate enthronement of God, and the book of Psalms is no exception. Futato states that the dominant theme of the book is the kingship of God.[36]

Not only is God’s enthronement a future certainty, it is also a present reality for all who are now in Christ. God’s enthronement directly addresses the nature of his presence with his people, but the way that God was present with his people in the first covenant was different than the way that he is present with his people in the new covenant, just as it will be different in the eschaton. This section will explore some key ways that God’s presence was made manifest in the Old Testament.

First, I must return to the Hebrew verb yashab. As noted earlier, this verb is commonly found in the Old Testament and used both for God and man, with obviously differing connotations depending on subject. In comparison, the Old Testament also uses the word shākan for God’s dwelling. This word is primarily concerned with God’s location, whereas yashab “expresses the concept of Yahweh’s independence.”[37] Furthermore, “when God is the subject of the root yšb, it is best to understand it as God’s enthronement rather than his location.”[38]

There is a sense of the theological reality of God’s sovereign rule and reign that can be gleaned from the differences between these two words. God’s enthronement is not bound to time, space, or circumstance; God chose to limit his presence to time and space only as it was made manifest to Israel under the old covenant. “He is free, for nothing can bind, restrict, or limit God. He may enter into time and space, but he is not bound to it. His throne is in heaven ([Psalm] 2:4), but his footstool is in Jerusalem.”[39] This point further supports the argument that the “praises of Israel” is representative of God’s presence in the temple and not an enthronement on the actual praises of Israel. God chose to dwell in a special way among his people in the Old Testament as an expression of his covenant towards them; it was not dependent upon anything that they could bring to him in worship.

Concerning the nature of God’s presence in the Old Testament, James Hamilton Jr. explains, “the Old Testament teaches that God was with his people by dwelling among them in the temple rather than in them as under the new covenant.”[40] God first chose to dwell among his people in the tabernacle of Moses before he then chose to dwell in the temple in Jerusalem. The book of Exodus provides detailed, intricate instructions for the tabernacle and how it should be constructed, all of which were meant to point to God’s glory and the need for mediation between sinful man and God’s holiness. God did not choose to dwell in the tabernacle and temple in a general sense, but more specifically his presence was represented by the ark of the covenant. VanGemeren argues:

The “temple” was God’s sanctuary, his palace on earth. The OT recognizes gradations of holiness; while the whole land was holy, Jerusalem was more sacred. The outer court was holy, the Holy Place was holier, and the Holy of Holies was Yahweh’s “dwelling,” the d ͤbîr (“the Most Holy Place”). . . . The d ͤbîr was cubic in shape and housed the ark of the covenant, which symbolized the presence of Yahweh.[41]

The relationship between God’s presence and his holiness is unambiguous.

Perhaps most significant to the detailed instructions for the construction of the tabernacle/temple and the ark of the covenant is the concept that God’s dwelling place was to be an earthly representation of his heavenly one. If the temple was to be an earthly representation of the LORD’s heavenly temple, then the ark of the covenant was the earthly representation of his heavenly throne. According to VanGemeren, “the symbol of God’s eternal . . . and temporal rule is the ark. The Israelites had no problem conceptualizing his rule; they envisioned Yahweh as being enthroned on earth, in the temple, on the ark, and between the cherubim.”[42] Therefore, an understanding of the enthronement of the LORD under the old covenant must take into account that the Israelites would have envisioned his presence as being located in the temple; and the seat upon which he was enthroned was between the cherubim on the ark of the covenant. This concept further elucidates the psalmist’s connection of the holiness of God in the first colon of Psalm 22:3 with his enthronement in the second colon.

Summary

Consequently, God’s presence in the Old Testament must be understood as located in a special way with the tabernacle and later the temple. This is essential in providing support for understanding the theological reality of God’s sovereign rule as the emphasis for Psalm 22:3 rather than an expectation based on the worshiper’s activities in the temple.

Implications for Contemporary Worship Practice

Several implications can be drawn from this interpretation. First, the similarities and differences in God’s presence in the old and new covenants should be recognized. Under the old covenant God’s presence was made manifest in the temple—more specifically within the Holy of Holies and between the cherubim on the ark of the covenant. However, this localized presence changed with the advent of the new covenant and the person and work of Christ. In John 4 Jesus teaches that with his coming worship would no longer take place in Jerusalem at the temple, but rather “in spirit and truth” (John 4:24). Moreover, worship in spirit and truth is made possible through the once for all death and resurrection of Christ (Heb 10:1–18). Furthermore, John’s gospel states that Christ himself is the temple of God, and Paul and Peter explain that the church has become the temple of God, both individually and corporately. As Andreas Köstenberger submits, “In Old Testament times, God dwelt among his people, first in the tabernacle (Ex. 25:8; 29:45; Lev. 26:11–12), then in the temple (Acts 7:46–47). In the New Testament era, believers themselves are the temple of the living God (1 Cor. 6:19; 2 Cor 6:16; cf. 1 Peter 2:5).”[43]

God indwells every person who is regenerate in a new covenant context. Additionally, participation in the gathered church, the covenant community, is a necessity for every believer to know the fullness of God’s presence. This participation is not conditional upon a specific church’s ability to offer certain kinds of praise, but it is rather a theological reality for every true church in Christ by the power of the Spirit and because of God’s sovereign grace. God calls his people out of the world and their individual lives to worship him corporately in spirit and truth.

Second, considering the difference in God’s manifest presence in the Old and New Testaments, affirmation must be given for the necessity of use of the Psalms in Christian worship. New covenant believers can use the Psalms with an appreciation and recognition that they have a fuller picture of God’s historic plan of salvation. About the Psalms John Calvin wrote:

Here the prophets themselves, seeing they are exhibited to us as speaking to God, and laying open all their inmost thoughts and affections, call, or rather draw, each of us to the examination of himself in particular, in order that none of the many infirmities to which we are subject, and of the many vices with which we abound, may remain concealed.[44]

The Psalms form the prayers of Christians and teach them how to express the range of emotions that are appropriate for the Christian life.

Finally, the question of appropriateness and necessity for using Psalm 22:3 as a proof-text to support the statement that God inhabits the praises of his people remains. As presented above, Psalm 22 is a psalm of lament, which turns to a declaration of praise to God in its final verses. In context verse three provides an expression of confidence in the LORD’s holiness and the reality that his presence is near. This statement appears to be one of theological reality. However, in the context of a contemporary worship service, “God inhabits the praises of his people” is often used as an exhortation to encourage greater levels of participation and a hermeneutic for connecting worship to individual expression. Christians must reevaluate their use of this expression and its perception and reception in the minds of congregants.

Moreover, the central purpose of the entirety of Psalm 22 must be strongly considered. Goldingay proposes one compelling possibility:

[Psalm 22] offers a most suggestive concrete expression of a mature spirituality that is able under pressure to hold on to two contradictory sets of facts. The Psalter presents it as a model for the prayer of ordinary Israelites or Christians when they experience affliction.[45]

The first set of facts involve the believer’s feelings of being overwhelmed, that these feelings may be due to persecution, and a feeling that God has abandoned them. The second set of facts, which is to first “remind God and ourselves of God’s past acts of deliverance toward the people of God,” to remember God’s faithfulness to his people individually, to “explicitly urge God to change” and bring deliverance, and the belief and realization that God will respond. This prayer provides a model for true confidence and trust of God in the midst of the most adverse circumstances of persecution.[46]

Furthermore, it is paramount to recognize the unforgettable connection of Psalm 22 with our Lord. The words of this psalm were spoken by the suffering Christ as he hung on the cross for the sins of his enemies. This point further impresses the reality that it is Christ alone who makes it possible for the indwelling presence of God with man.

Conclusion

Throughout this paper I have argued that God’s enthronement on the praises of his people is a theological reality that emphasizes God’s sovereign rule and reign over his covenant people rather than an anthropocentric concept of man’s responsibility in worship. My purpose was to emphasize the theological reality that God is present with his covenant people in both the Old and New Testament by the nature of his own faithfulness to his covenant and not dependent on the work of his people.

Does God inhabit the praises of his people? The answer is yes, when understood as a metonymy of adjunct representative of the temple—the individual Christian as well as the gathered church—where he makes his dwelling. God’s presence with his people is not because of the efforts that the redeemed bring or the particular songs they use to bring praises to him; and it does not correlate with the amount of physical effort that is exerted. God inhabits the praises, Scripture reading, prayers, preaching, singing and any other Scripturally ordained means of worship that they bring to him by faith as his covenant people, because he is sovereign over all and he has chosen to make his dwelling on earth with his people as a guarantee for the inheritance that awaits all who are in Christ (Eph 1:13–14).

[1] Matthew Sikes is a Church Music and Worship PhD student at Southwestern Seminary and Pastor of Discipleship and Worship at Pray’s Mill Baptist Church in Douglasville, GA.

[2] For example, Darlene Zschech, Extravagant Worship (Minneapolis: Bethany House, 2002), 57; Bob Sorge, Exploring Worship: A Practical Guide to Praise and Worship (Canandaigua, NY: Self-Published, 1987), 7; David K. Blomgren, Douglas Christofell, and Dean Smith, eds., An Anthology of Articles on Restoring Praise and Worship to the Church (Shippensburg, PA: Destiny Image Publishers, 1989), 22; Judson Cornwall, Let Us Praise (Plainfield, NJ: Logos International, 1973), 24–25.

[3] Zschech, Extravagant Worship, 54–55.

[4] Swee Hong Lim and Lester Ruth, Lovin’ on Jesus: A Concise History of Contemporary Worship (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2017), 111–12.

[5] Cornwall, Let Us Praise, 26.

[6] Judson Cornwall, Let Us Worship (South Plainfield, NJ: Bridge Publications, 1983).

[7] Sorge, Exploring Worship.

[8] Lim and Ruth, Lovin’ on Jesus, 113.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid., 124.

[11] Blomgren, Christofell, and Smith, An Anthology of Articles on Restoring Praise and Worship to the Church, 92.

[12] Ruth Ann Ashton, God’s Presence through Music (Elkhart, IN: Imaginataive Art Ministries, 1993).

[13] Lim and Ruth, Lovin’ on Jesus, 131.

[14] Robert Webber, “Enter His Courts with Praise: A New Style of Worship Is Sweeping the Church,” Reformed Worship 20 (June 1991), accessed October 5, 2018, https://www.reformedworship.org/article/june-1991/enter-his-courts-praise-new-style-worship-sweeping-church.

[15] See, for example, Allen P. Ross, A Commentary on the Psalms, Volume 1 (1–41), Kregel Exegetical Library (Grand Rapids: Kregel Academic & Professional, 2011), 50.

[16] Tremper Longman III, How to Read the Psalms (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1988), 51–62.

[17] Mark David Futato, Interpreting the Psalms: An Exegetical Handbook, Handbooks for Old Testament Exegesis (Grand Rapids: Kregel Publications, 2007), 122–23.

[18] Sigmund Mowinckel, The Psalms in Israel’s Worship, Biblical Resource Series (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004), 2.

[19] Longman, How to Read the Psalms, 45.

[20] Ibid., 95–122; Futato, Interpreting the Psalms, 24–25.

[21] Ross, A Commentary on the Psalms, 1:526.

[22] Ibid., 1:528.

[23] John Goldingay, Psalms, Volume 1: Psalms 1–41, Baker Commentary on the Old Testament Wisdom and Psalms (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2006), 323.

[24] For instance, verse three speaks directly of the praises of Israel and then the shift in tone that begins in verse twenty-two is almost exclusively focused on praising God in a corporate, congregational setting.

[25] Willem A. VanGemeren, Psalms, ed. Tremper Longman III and David E. Garland, revised ed. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2008), 237.

[26] Goldingay, Psalms, 1:327.

[27] Ross, A Commentary on the Psalms, 1:522.

[28] Goldingay, Psalms, 1:327–28.

[29] Ross, A Commentary on the Psalms, 1:522, n.4.

[30] Ibid.

[31] R. Laird Harris, Gleason Archer, and Bruce Waltke, eds., Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament, vol. I (Chicago: Moody Press, 1980), 922.

[32] Ross, A Commentary on the Psalms, 1:532–33.

[33] Ibid., 1:99. Emphasis added.

[34] Ross cites many examples of OT use of metonymy, see ibid., 1:96–101.

[35] Harris, Archer, and Waltke, Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament, 1:922.

[36] Futato, Interpreting the Psalms, 72.

[37] VanGemeren, Psalms, 931.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] James M. Hamilton Jr., God’s Indwelling Presence: The Holy Spirit in the Old and New Testaments, ed. E. Ray Clendenen (Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2006), 25.

[41] VanGemeren, Psalms, 932.

[42] Ibid., 934.

[43] Andreas J. Köstenberger, ”John, ” in Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2007), 141.

[44] John Calvin, Commentary on the Book of Psalms, trans. James Anderson (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1963), xxxvii.

[45] Goldingay, Psalms, 1:340.

[46] Goldingay, Psalms, 1:341.